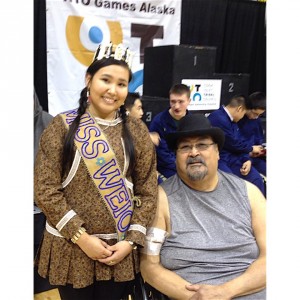

A legend of traditional Alaska Native games has died. Big Bob Aiken, known as the ‘The World’s Largest Eskimo’ still held records for the Indian and Eskimo stick pull competitions. He believed deeply in the original purpose of the games.

In a phone conversation last July from the World Eskimo Indian Olympics or WEIO games in Fairbanks, he said the games were meant to be friendly competition that tested strength and revealed who would be a good hunter.

“Then if you knew exactly what you are capable of, you’d have a better chance of surviving in an incident that happens out in the wilderness. Because I hurt myself one time and I knew I was capable of by these games. So we were raised to survive whatever happens. That’s who we are, that’s how we grew up.”

Lew Freedman worked as a reporter for the Anchorage Daily News in the late 80s and became a friend of Bob Aiken as he covered him in Fairbanks at the WEIO games. He said although Aiken didn’t have his own children, he cared for all children involved in the games and was an important diplomat.

“The kids would like swarm around him and he was interacting with everybody.You know it was sort of like, we can’t make a decision about anything without seeing what Big Bob thinks about it and he was that kind of fella, you know he just stood out with a big personality to go with his big size.”

Freedman says he thinks the final year that Aiken competed in strength games was 1989 and Big Bob intended to retire with all of his gold medals and one more win.

“There was a big surprise that year because a new guy came on the scene, Brian Walker from Eagle River, who was also a big guy but nobody was as big as Big Bob at the time. And Brian beat him, so actually Big Bob lost at the end of his career, kind of probably completing the thought process that it was time to retire.”

Bob Aiken was a life long Barrow resident until the last few years when he had to live in Anchorage for dialysis treatments. In recent months he had also developed a heart problem. Freedman says he was a warm man with a great sense of humor and even with his health trouble, he never missed the games, acting as an MC, or an official and remained a large figure both physically, at 6 foot 4 and as a champion of performing the games correctly.

“But more than anything else he had a sense of tradition and heritage and wanted that to be passed on to future generations. That was the most important to him. You’d have to say he was a keeper of the flame and that was what really integral to his continuing involvement with WEIO was, through the rest of his adult life.”

Big Bob Aiken was 62 years old and died in Anchorage on Tuesday.

Here’s the transcript of an interview APRN’s Lori Townsend did with Bob Aiken in July 2015.

TOWNSEND: How old were you when you were first involved in WEIO?

AIKEN: Back in the 60s…. about 16, 17.

TOWNSEND: Had you done this type of endurance and strength test before WEIO?

AIKEN: I was born into to it and grew up with it.

TOWNSEND: Tell me about that.

AIKEN: Growing up in the village, we were exposed to it since we were kids and we grew up with it, all the games.

TOWNSEND: Why were the Games important? What did they help you do when you were growing up?

AIKEN: These games were given to our grandparents which were given to them by their grandparents which were given to them by their grandparents. These aren’t just games, these are potlatch events. Friendly competition between neighbors or neighboring villages. They’d come together after a successful hunt, it’s part of sharing. The men would do a friendly competition. The grandparents brought them on so they would know who would be a good provider. All the strength events would lead to being a good hunter, a good provider.

TOWNSEND: So it was a way of finding out who would most likely have success in extreme weather, is that how it was seen?

AIKEN: Yeah and the dad would have to know what his son is capable of. By these games, they’d bring out the best to an individual. They were never meant for competition, but over the years that’s what they evolved to. It’s unhealthy. Somewhere along the line, it picked up this competitive attitude and it wasn’t supposed to be there but it is.

TOWNSEND: Tell me about when you were in the Games and were very well known. You were mown as the ‘World’s Largest Eskimo’ — how did that come about?

AIKEN: Well, my growing up years, my grandfather was 6’6’’ and he was half Irish. And his father was the one that came up from Ireland to be on a whaling ship. It got stranded in Barrow. We’re the product of that Irish-Inupiaq. How we grew up, we grew up Inupiaq. The Irish is still there by how tall we are. And the last name Aiken was pronounced Eye-kin in Ireland. We grew up with our grandfather, my mother’s dad, all Inupiaq, full blooded and that’s where we got our wisdom from. Growing up Inupiaq.

TOWNSEND: How tall are you?

AIKEN: 6’4’’ my grandpa was 6’6’’. They said I have his genes.

TOWNSEND: What were some of your big accomplishments in the Games?

AIKEN: To pass on what our elders passed on, to the letter. There’s some changes that were trying to come about by a couple of entities and what normally would come from our elders would be to correct them and show them how it’s done and that was the biggest part of my being there, to make sure tradition is passed down to the letter.

TOWNSEND: Do you still act in that role today? … Helping young people and making those corrections?

AIKEN: Yeah, unfortunately everybody wants to change to make easier games. I told them, that’s not what it’s about. The games were made exactly the way they are and if we change them it would have to go back to our grandpa’s grave and ask him politely if we can change it. Knowing that they won’t get an answer, the games were set the way they are and they will stay the way they are as long as I’m still breathing.

TOWNSEND: I know you’ve had some health challenges. Can I ask how you’re feeling and is it OK to ask how old you are?

AIKEN: I’m 62 now. I’ve been going through health problems. I lost a kidney couple years back. Heart valve is weakening and just kind of feeling my age I guess.

TOWNSEND: You’re in Fairbanks right now. Are there some things you’ve seen that really stand out as noteworthy?

AIKEN: Well, I haven’t even, I’m too tired to go to the arena. I watched one game and then had to go back because I’m losing strength, I think my body’s about had it.

TOWNSEND: I’m sorry to hear that. Do young people know you and still come to you for advice to help them in the Games?

AIKEN: Yes, sometimes they do.

TOWNSEND: How do the games in Fairbanks compare to what you were doing in the 60s?

AIKEN: There wasn’t that much competition. It was just something we’re trying to bring t the world to make aware of these games and somewhere in there, competition jumped in and ruined everything. Our elders a prideful look, even pride, stubborn pride, showed an ugly face and our competition should have never been there. We try to put on showmanship, which our elders would have shunned a long time ago. What we have left is a knowledge about who we are and what we are. My uncle, without saying a word made a statement to the world. Some reporter took a picture of a piece of muktuk, which we love and a pair of mukluks, which we wear and he would say, I am Inupiaq, by that, he made a silent statement of who we are and who we still are, we still will be tomorrow. God made us this way.

TOWNSEND: What would you like to see going forward to make the games more traditional?

AIKEN: When we were growing up, we were gathered in a cutagee, a public meeting place or potlatch and all the whaling captains, all the hunters would bring their catch, they’d cook it up, then the whole community, then they’d invite the surrounding villages to partake of their blessing. This is how these games came about. They weren’t in competition, they were just a test of endurance, agility, ability, the test was to each individual, what they are capable of. Today you don’t see that. I’d like to see that again.

TOWNSEND: So you’d like to see it go back to competitors testing themselves rather than competing against others?

AIKEN: Yes. Well, that’s what it is, what it looks like. There was no first place, second place or third place, it was just all around…..if you could see what you were capable of, you had a better chance of surviving in the wilderness. I hurt myself one time and I knew what I was capable of by these games so. The western region logic is just give up and die if you get hurt, but we weren’t raised that way, we were raised to survive whatever happens. Always a possibility of surviving, that’s who we are, that’s how we grew up.

TOWNSEND: Do you think there’s still value in what young people are learning in working out and trying to get their skills up to do these competitions and testing their own strength and ability? Is this still valuable?

AIKEN: Yeah, very valuable to an individual. And to their peers and parents, there’s something of value to respect an elder who passed it on.

TOWNSEND: Is there anything else you’d want people to know about WEIO and the games themselves and your long history with it?

AIKEN: Well, I’ve been involved with arctic winter games, native youth Olympics, I grew up with our traditional games since day one and all I’d like to say is the cutagee atmosphere that we used to have, these games were brought to Indian Country, out of respect to the Koyukon Athabascans, I would ask before I did anything because I’m on their territory. I would ask a Koyukon Athabascan elder, permission to be on their land to do our traditional games. That is a lot of respect that people don’t see very often. The tribes around here, a lot of times don’t take kindly to trespass. So a lot of times we have to ask an Athabascan elder for permission to do these games. Tribal respect for each other. But they gladly invite us back, which is good.

TOWNSEND: Is that still happening today?

AIKEN: Yeah, there was an elder that welcomed us. By that, we were welcomed to their land. I’m glad I saw that. It encourages me to keep showing who we are.

TOWNSEND: Do you still have records you hold from the ’70s and ’80s?

AIKEN: Most have gone by and young people have beat them, but there are still some that I still hold.

TOWNSEND: Which ones are those?

AIKEN: Indian stick pull, Eskimo stick pull, leg wrestling, one more I forgot. Most of these are strength events.

Lori Townsend is the news director and senior host for Alaska Public Media. You can send her news tips and program ideas for Talk of Alaska and Alaska Insight at ltownsend@alaskapublic.org or call 907-550-8452.