Commercial fishing in Alaska is a multi-billion dollar industry. But every year, billions of dollars are lost to illegal fishing around the world. A new satellite-based surveillance system makes it easier to track illegal fishing. But some fishermen aren’t ready for Big Brother watching their every move.

Worldwide, over-fishing is a huge problem. Jacqueline Savitz, vice president of the conservation group Oceana, says populations of big fish, like halibut, have dropped 90 percent. But the fish can rebound when their habitats are protected.

“We actually see fish stocks coming back and getting to levels where they’re sustainable, so we can continue to live off the interest, if you will, and not fish down the principal,” Savitz said. “But we also have a problem with illegal fishing. It’s about a $23 billion industry globally.”

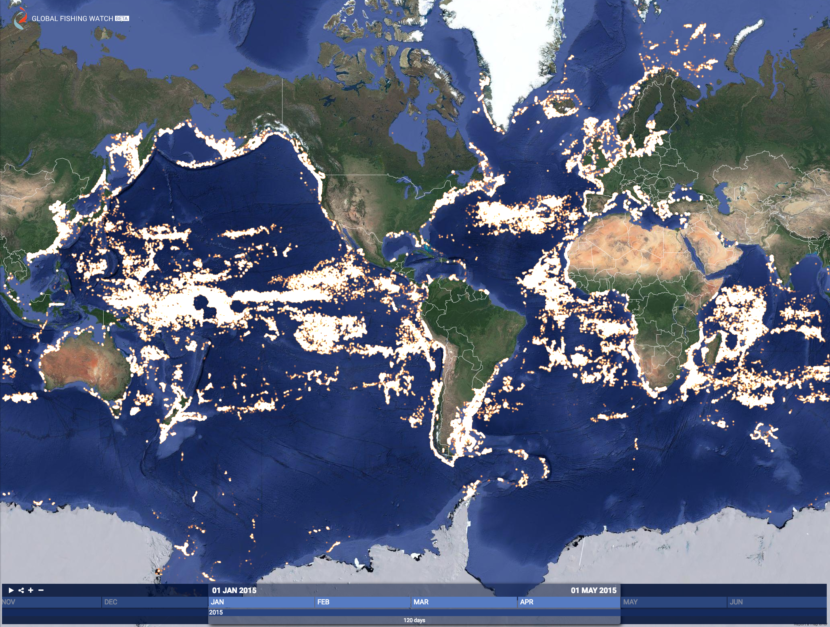

Now, there’s a new tool for people who want to prevent illegal fishing: Global Fishing Watch. It’s a free, web-based, interactive map of the world’s traceable commercial fishing activity, dating back to January 2012.

It’s based off information gathered from vessels’ Automatic Identification Systems (AIS). The boats broadcast signals including their location, who they are, and where they’re headed.

Not all boats have to use AIS. Currently, the International Maritime Organization only requires it for large vessels like big oceangoing cargo ships and certain vessels on international voyages

While AIS technology has been around for a while, this is the first time all its information is publicly available.

As ocean traffic increases, Savitz hopes Global Fishing Watch will increase accountability. She points to Alaska’s waters as an example

“There’s a lot of change happening up there with the changing climate and potential new shipping routes through the Arctic and the Bering Strait,” Savitz said. “There are going to be areas that are protected. How are we going to know if they are really being protected?”

That’s what this project hopes to do. But fisherman Roger Rowland doesn’t like the idea that everyone can track his vessel. He wants to protect his fishing hot spots.

“With my salmon fishery, I don’t want people knowing where I am,” Rowland said. “Since I’m not legally required to have it, I turn it off.”

Rowland owns a 58-foot seiner based in Unalaska. Because his boat is small, he isn’t required to constantly run AIS.

Even though Rowland likes his secrecy, he thinks Global Fishing Watch could be helpful for certain fisheries.

“When I’m pot cod fishing, I do have legal areas where I cannot go,” Rowland said. “My boat cannot go inside a ring around a sea lion rookery, and so it’s good for that. Nobody is sneaking in there because someone is watching.”

John Amos is the president of SkyTruth, a nonprofit that uses technology to highlight what’s happening in the environment. He says even though fishermen like Rowland might not want to be tracked, there’s a benefit for people who play by the rules.

“People care about where and how their food is being produced,” Amos said. “Here’s an opportunity for fishing vessel captains to create personal relationships with their consumers at the seafood market or at the restaurant table and say, ‘Look, we are the good guys, and we’re going to show you.’”

There will always be fishermen who turn off their AIS, but Amos believes Global Fishing Watch will help crack down on the amount of unregulated and unreported fishing as well as empower individuals to monitor patches of ocean they care about.

Zoe Sobel is a reporter with Alaska's Energy Desk based in Unalaska. As a high schooler in Portland, Maine, Zoë Sobel got her first taste of public radio at NPR’s easternmost station. From there, she moved to Boston where she studied at Wellesley College and worked at WBUR, covering sports for Only A Game and the trial of convicted Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.