Our country is celebrating the one hundred fiftieth anniversary of the Civil War (1861-1865). On a recent trip East, husband Dave and I tried to remove the surreal when imagining neighbors killing neighbors or our non-white relatives as slaves.

We flew to National Harbor near DC for Dave’s American Bankruptcy conference. Most of the time we avoid renting cars in big cities; fortunately our kids live near subway lines. Gleefully, we let people know our preferences for snowy Alaskan winters over being stuck on freeways, changing lanes high above ground on what are affectionately called ‘spaghetti junctions.’ Add torrents of rain and a high pollen count back East, and April in Anchorage with its sandy streets, remnants from icy roadways, starts to look good.

Instant ‘add water and stir’ National Harbor, once a plantation, opened for tourism in 2008. It’s a convention center of sameness–concrete and glass structures strewn amongst manicured gardens with chain-boutiques and eateries, and a few faux Colonial homes. OK, the bleu cheese burger at the Cadillac Ranch the night we arrived after sleeping across America on Alaska Airlines, was delicious.

Warning, transportation to and from National Harbor is frustrating for those who want to experience the immediacy of an urban vacation. We had been told to just hail a water-taxi for a quick ride to Alexandria across the Potomac. There you can walk up King Street to the Metro station and train into DC. But apparently in spite of the lure of cherry blossoms, April is still off-season and getting across the river is intermittent.

So we paid forty bucks for a cab to see the exhibition at the Smithsonian Museum of American Art, The Civil War and American Art. This museum also houses the National Portrait Gallery and has several gift shops and a café adjacent to its large glass atrium where visitors can take out soup and salad under the Washington sky, regardless of weather. With our kids on both coasts and one in Alaska, Dave and I think of America as one continuous subdivision. No matter how many photographs of dead Civil War soldiers shoveled into mass graves I’ve seen, the idea of a war between states continued to be surreal as I approached The Civil War and American Art.

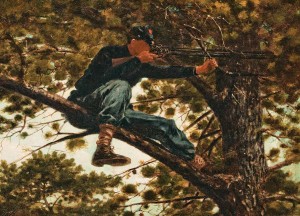

Winslow Homer is very present. No wonder, his lithographs for Harper’s Weekly graced mahogany tables, bringing the carnage of war into Victorian parlors. Homer’s painting Sharpshooter (1863) depicts the indifference of guerrilla warfare as a soldier positioned in a tree waits to kill an enemy, caught off-guard.

This was not gentlemanly warfare of yesteryear where lining up in formation and calling it quits at sundown was the etiquette. Sharpshooting was voyeurism gone haywire. These ace riflemen, good at hunting game, were often gentlemen farmers, now hunting down their neighbors. Homer depicted the tree’d sharpshooter in a similar way that a men’s adventure magazine would position an advertisement for hunting gear.

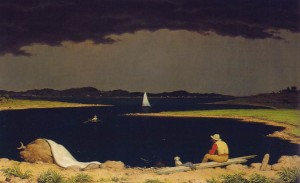

Martin Johnson Heade’s Approaching Thunder Storm (1859) shows squally weather, a common metaphor for the inevitability of this war. A man and his dog sit by a bay helplessly observing the approaching storm. A sail dries in the foreground but its boat is missing. Heade made the water darker than the stormy horizon, forcing the viewer to focus downward into the bottomless bay of the foreground rather than look off into the clouds.

Societal answers were not somewhere out in the wild blue yonder but could be found within one’s soul. The country’s doom needed to be addressed now and not in the distant future. This exhibition attempts to remove some of the surreal, however I found the beauty of the compositions overtook and prevented complete empathy.

Continuing to find our stay at National Harbor akin to being stuck in Pooh’s honeypot, we gave in to Hertz and drove our rental fifty miles south to Fredericksburg, the scene of four major Civil War battles, hoping to experience the surreal we had not found at the Smithsonian. My great-grandfather John R. Johnston and his brother George fought with the Union army. I’ve heard cavalry division and supply depot, maybe, were their jobs.

Apparently, the Johnston brothers loved the Grand Army of the Republic parades and reunions. It’s been rumored Dave’s relative had paid to be excused from war duties; it’s a family-OK as the gentleman remained a Yankee sympathizer. Spending an afternoon in Confederate territory, the land of rebellion, added to inventing a narrative for ourselves.

As children growing up in Boston, we were told all Confederates were evil. Of course, no one had bothered to tell us Northerners also owned slaves or that New England merchants benefitted from the cotton trade too. One of my on-line PhD colleagues lives in Southern Virginia. I imagined if the war were still raging, I wouldn’t be allowed to email her. Then I remembered the Civil War forgot to supply computers.

We drove down Fredericksburg’s main drag of brick and lap-streaked buildings remodeled to accommodate restaurants and gift shops. A window sign read “Civil War bullets, a dollar.” We parked by the Rappahannock River, the site of General Burnside’s blundering. His pontoon bridges didn’t arrive in time so Robert E. Lee was able to block Union crossings. I don’t know what the river looked like one hundred fifty years ago, but today you could wade across. We watched joggers and dog walkers enjoying the bike path.

Hungry, we found Goolrick’s Drugstore. It’s been on Caroline Street since 1890, one of the oldest continuous operating soda fountains in the US. Dave and I sat at the counter and ordered chicken salad sandwiches and Coke. The pharmacist lets customers use the bathroom behind the prescription counter so I ventured to the storage area beyond a large black/gold safe sitting on buckled floorboards. The separating grain in the planking reminded me of Tiltons paper store on Main Street, Edgartown, Mass. As a child in the fifties I would accompany my father to buy The Boston Herald. Goolrick’s rotting floor brought back memories of grape and licorice gum flavorings impregnated into Tilton’s floorboards.

Continuing into the surreal, we munched pickles and crunched potato chips imagining that Goolricks must have experienced racial turmoil, as Blacks were forbidden to eat in white establishments until the sixties. Seated today at the drugstore’s few tables and stools were locals of all color, age and mobility. Afterwards, we found the Fredericksburg Museum which proved disappointing.

Now, I’m a museum snob and suggest visitors make sure a museum has a café and gift shop or beware of ending up in an establishment resembling grandma’s attic. OK, I’ll give the Fredericksburg Museum a pass as they had recently experienced water damage and several docents were jumping to divulge the town’s history to us. The seven dollar admission didn’t give us much though: a hair from George Washington and a few dioramas depicting ransacked houses and panicked locals fleeing the Yankee takeover.

We drove a few miles to the Fredericksburg Battlefields run by the National Park Service. Although their mini-museum had the usual: a drum, a surgical kit and few moth-eaten uniforms, the reenactment video was well done. Driving or hiking into the park is an inexpensive way to spend an afternoon. Like Gettysburg, only smaller, visitors need their imaginations.

We used our last hour before driving back to DC to tour Chatham Manor. Built in 1771 on the Rappahannock, this Georgian plantation was run with slave labor. Now owned by the Park Service, docents describe how the house echoes its past: Washington was a frequent guest, the Union army used it as a field office thus accommodating Lincoln. After General Burnside’s defeat, twelve hundred casualties were sent to Chatham, which became a makeshift hospital, staffed by Clara Barton and poet Walt Whitman who came looking for his wounded brother.

Apparently, Whitman’s shock at seeing piles of amputated appendages stacked under trees inspired him to volunteer. Dave and I watched a reenactment video in a parlor that once was a makeshift operating room. After the Smithsonian exhibition and our drive through now touristy Fredericksburg, trying to imagine the horrors of war wasn’t working for me. Perhaps I came the closest in Chatham’s makeshift operatory while trying to envision the bloody flooring, now carpeted.

I knew Clara Barton had grown up in North Oxford, Mass., adjacent to the farm that belonged to my Wellington great-grand parents. As a child, grandmother Gladys had met Clara Barton. Perhaps in between tending to the traumatized souls she had gazed out onto the river or looked up to the high ceilings, providing an aesthetic break from the hell surrounding her. Dave was told his grandmother had been held up to watch President Lincoln’s funeral procession in 1865. Personal connections and visual reminders are all that’s left of the surreal.

Before flying home to Anchorage, Dave and I flew to Atlanta for a Portrait Society Conference and a hug from Katie Stenzel, our adopted niece from Cambodia. At our hotel, the CBS evening news reported on segregated proms. On the website the article reads, “It may be 2013, but students at a Georgia high school made national headlines Saturday night holding their first-ever integrated prom…segregation is still very much alive in the school system.” Sadly, we’re not done with the surreal.

(The Civil War and American Art Exhibition moves to at the Metropolitan Museum May 27- September 2, the catalog is at Amazon, the CBS article is online.