As educators gear up for the school year, there is one Alaskan civil rights activist from Nome that they may want to include in their history lesson plans.

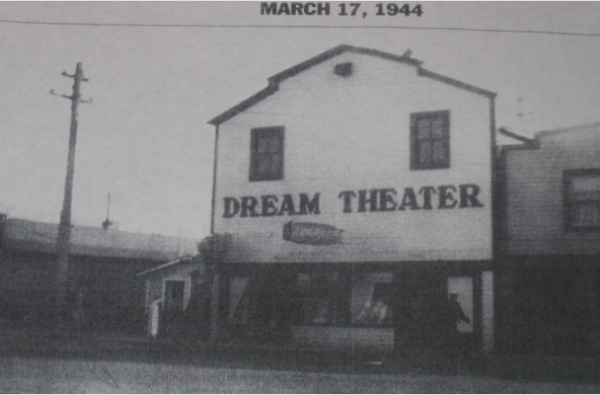

Back in 1944, a 15-year-old Alaska Native girl named Alberta Schenck stood up against the segregated seating policy at Nome’s Dream Theater. Her case, paired with Elizabeth Peratrovich’s, was eventually instrumental in the passing of the 1945 Anti-Discrimination Act in Alaska. That was 10 years before Rosa Parks refused to give up her seat, and nearly 20 years before the passing of the Civil Rights Act.

“Students are very well-versed about Rosa Parks, which is wonderful,” says Nome resident and longtime educator Barb Amarok. “But learning about people from their own community, region and state helps them to realize they’re capable of doing positive things for others. It gives them the message that who they are and where they come from is very important.”

While pursuing her doctoral degree in Indigenous Studies at University Alaska, Fairbanks in 2008, Amarok decided to focus her research on the Dream Theater after reading about an incident of discrimination her own family had experienced there. As part of her research, she interviewed five local elders. From Shirley Temple series to 25-cent movie tickets, the elders listed off plenty of fond memories of the Dream Theater, but the conversation turned more somber when they described the segregated seating sections.

“There were three blocks of seats, the middle block was for white people, the one on the east side was for breeds, quarter breeds and half breeds, and the block on the west side was for three-quarter and full blood natives,” said Gary Longley during his interview with Amarok. Longley was also Alberta’s first cousin. “And then they had the balcony…well, that’s where the real old natives sat.”

Amarok also conducted a phone interview with Alberta Schenck the year before she passed away to hear the full story of what happened. Alberta described two related instances of discrimination. The first was when she went with a date, sat in the white section and was asked to move. When she didn’t, she was forcefully ushered out of the theater. Alberta later returned to the theater where the ticket seller prohibited her from entering.

“Daddy said, ‘If she touches you, you hit her’ and I did,” Alberta said. “And that’s when the police came and got me. I was 15 years old and I got mad. I was mad as a hornet at the time.”

The day after her father bailed her out of jail Alberta wired a message to Governor Ernest Gruening. With the help of a lawyer named O.D. Cochran, Alberta’s case was used in support of anti-discrimination legislation in Alaska.

“Alberta’s letter to the territorial legislature had a lot to do with the Anti-discrimination law of 1945,” Amarok said.

While Amarok was working on this project seven years ago, she promised elders that eventually their voices and Alberta’s story would be brought to classrooms in Alaska and beyond. Through a collaboration with KNOM Radio, a 30-minute version of Alberta’s stories will be paired with a lesson plan for educators. Amarok says Alberta’s story includes lessons and sentiments that need to be heard today.

“We can still come to follow ways of thinking that are not best for the community,” Amarok said. “We need to be able to take a step back and really question whether or not certain practices are for the best and work for social justice.”

That’s what Alberta did and it’s what Amarok hopes her story will inspire in students.

To hear the full Story49 episode about Alberta Schenck and the Dream Theater and access the lesson plan, you can visit knom.org.