August’s essay was about the Institute for Doctoral Studies in the Visual Arts (IDSVA) I recently joined. My first IDSVA assignment was spending last June in a Tuscan castle listening to art theory and writing essays. Afterwards, the group boarded a train for Venice which is where this essay begins.

Venice’s Santa Lucia railway station is on the Grand Canal, my first clue that getting around this watery city meant using the aquatic bus system, Vaparettos. IDSVA stayed on Lido Island, a typical resort with over-priced boutiques, ice cream vendors and beaches with cabanas. Lido translates to beach, hence lido decks on cruise ships. After more lectures, I left the IDSVA gang for a week of sightseeing with husband Dave.

It’s true, I’d rather be in an art museum than most anywhere. I’ve been going to New York’s Metropolitan since I could walk. American nineteenth century industrialists like Frick or Havermeyer scooped up whole rooms of foreign art, including wall paneling and floor boards, bequeathing much to domestic museums. Today, curators pay strict attention to how the art is arranged.

I found Italy’s classical paintings hung haphazardly, their mythical narratives crowd ceilings and often drip their way down around windows, finally spilling onto door jams. Forests of statues wait to be bumped by tourists herded through galleries by microphoned docents. Italian museums have few bathrooms and eateries, catalogues were often out of print. Strolling through miles of “Annunciations” grew tedious, but suddenly I would encounter a gem.

Peggy Guggenheim’s Venetian palazzo on the Grand Canal, part of the Guggenheim museums worldwide, is a jewel. Dave and I got off the Vaparetto at Accademia, and walked the back alleys to Peggy’s gated entrance, a piece of Americana abroad. Peggy’s wealth came from father Benjamin, who drowned on the Titanic. In 1938, she opened a London gallery, Jeune, learning much about modernity from British historian Herbert Read.

By 1939 the European avant-garde was panicking to escape the tyranny. Works were selling at bargain prices and Guggenheim was there with her checkbook and a list from Read. Peggy spent the war in America but returned to Venice to renovate PalazzoVenier dei Leoni. The hand-welded Falkenstein gate opens onto a sculpture garden behind her waterfront palazzo. An adjacent building now features a cafeteria and gallery for traveling shows.

Peggy and her Lhasa terriers are buried near a Yoko Ono “Wish Tree” (visitors hang paper wishes). College interns take tickets and become docents, telling visitors not to blow on the Calder mobile in the entryway. In Peggy’s white palazzo, bathrooms and bedrooms have become extra space for Picasso, Braque, Dali, Duchamp, she bought them all. Curious, her dining table is unusually narrow. I suppose Truman Capote (she put him on a diet) was expected to squish while focusing on Leger or the Archipenko sculpture.

The canal entrance has a dock for visitors who came by gondola. Today, photographs help visitors imagine Peggy diving into the canal alongside her grandchildren or entertaining Somerset Maugham on her roof deck. A nude on horseback, “Angel of the Citadel” (1950) by Marini sported a removable penis, now soldered, the original kept disappearing. Dave and I returned several times to eat burgers and fries on the glass-enclosed terrace overlooking the sculpture garden with Peggy’s large stone throne center-stage.

In 1942, the war forced the Venice Biennale to close—it reopened in 1948 with Peggy Guggenheim’s collection. This international exhibition that commenced in 1895 uses Venice’s historic arsenal, a shipyard constructed a thousand years ago that once mass- produced warships. Today the long buildings with remnants of railroad track assemblage (a la Henry Ford) becomes the fair’s focal point.

Over the years many countries have established their identity by building pavilions. Rope and sail maker tools have been replaced by conceptual art and looped videos. At this 54th Biennale, James Turrell surrounded viewers with colored light while Christian Marclay’s spliced movie bites “The Clock” (2010) become a reinvented twenty-four hour flick. His Hollywood clips show clock faces matched to the real time in a theater.

I stood before Tintoretto’s “Last Supper” (1592) then walked to nearby “Track and Field” (2011) an inverted tank with moving treads by Allora and Calzadilla, now a giant treadmill. Women from the US Olympic track team demonstrate their prowess by running on a war machine. Of interest, curators are often not from the country they represent. The Venice Biennale could stand a makeover, perhaps by adding some tropes found at Disneyland.

Dave and I left Venice for Florence and the Uffizi, luckily we pre-purchased tickets. Watching the movie “Tea with Mussolini” is a great way to experience these former offices now housing masterpieces like Piero della Francesca’s Duchess and Duke of Urbino or Botticelli’s Birth of Venus. We ate paninis in the roof café overlooking the crenellations of the adjacent Bargello, Florence’s first civic structure.

Afterwards we walked to the Basilica di San Lorenzo where the Michelangelo Medici tombs reside, surprisingly vacant of tourists. You can get close to these giant statues of Day, Night, Dawn, and Dusk and feel the weight of muscled bodies balancing atop the tombs of Lorenzo and Giuliano.

With only a few days to sightsee before flying back to Anchorage we boarded a double-decker bus and circled twice around Rome. This sounds a bit tacky but it’s a great idea when time is limited. We whizzed through narrow streets of stucco buildings, past the Coliseum and Circus Maximus, imagining gladiators and chariot races. On our last day clutching more pre-purchased tickets we saw the best art in Italy.

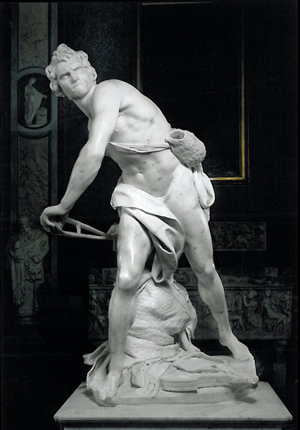

We took the Metro to the Borghese, a museum/villa built for Cardinal Scipione Borghese. It is said his collections were often acquired unscrupulously, nonetheless they were breathtaking. Bernini’s “David” (1623) is supposed to be a self-portrait. The slingshot, textured shot pouch hanging off David’s left hip, and his head of curly locks above his furrowed brow form a Renaissance triangular design element, all in marble. Unfortunately, visitors are only allowed two hours to walk through this treasure trove of Bernini’s sculpture.

Special thanks to NPR’s Rick Steves and his indispensible travel book “Italy.”