The movie, Big Miracle, released this month in theatres nationwide, begins with a Barrow bowhead whale hunt, so I will begin my series on the Great Gray Whale Rescue of 1988 with a bowhead hunt as well – actually, fragments of different Barrow hunts, culminating in the spring of 1988 – the same year that the rescue took place.

I was awestruck by the whale in the opening scene of the movie, in part because I have never seen a bowhead from quite that perspective in real life, yet I have seen them almost exactly like that in my dreams. The difference being that in my dreams the bowhead always turns upward, pulls the surface of the sea up in a dome with it until finally its snout breaks through the dome and then the water cascades down its sides as it climbs straight up through the air towards me.

The bowhead whale above breached in front of the whale camp of George Ahmaogak, Sr. during a time of cease fire. Elsewhere on the water, crews were in the process of landing two bowheads. Until that task could be completed, no further strikes could be made. This happened in the year 1994 – when I returned to the Ahmaogak camp nine years after my first sojourn with them.

This whale has been keeping the Iñupiat people alive now since the days of antiquity. To some, it may seem incongrous, but the Iñupiat people not only know the whale better than does anyone else, they have a deep love and respect for the bowhead whale, the likes of which is held by no other group of people. They depend on the whale, they need the whale, they know the whale, they respect the whale, they love the whale, they hunt the whale.

The Iñupiat and the bowhead have shared this sacred, life-giving relationship for thousands of years. In these modern times, the Iñupiat, a modern people, remain bound to the whale just as their ancestors were.

This is George Ahmaogak, who, in May of 1985, opened the door that allowed me to enter the world of the Iñupiat, and of whaling in particular. That May, I spent 12 days on the ice with him and his crew. It was a hard season. No whale was landed in Barrow in that time.

George taught me many lessons, some of them difficult. Chief among these lessons was one that I would hear confirmed many times by the elders afterward: a hunter must be skilled and stealthful, a hunter must also be respectful and generous toward others. No matter how skilled the hunter is, he is not skilled enough to land this great animal unless it first chooses to give itself to him.

The whale will only give itself to respectful, generous hunters, who keep their ice cellars clean and share their food with others – especially the elderly, the sick, and those who cannot hunt for themselves.

Hence, the title of my book, from which these pictures come: Gift of the Whale: The Iñupiat Bowhead Hunt – A Sacred Tradition.

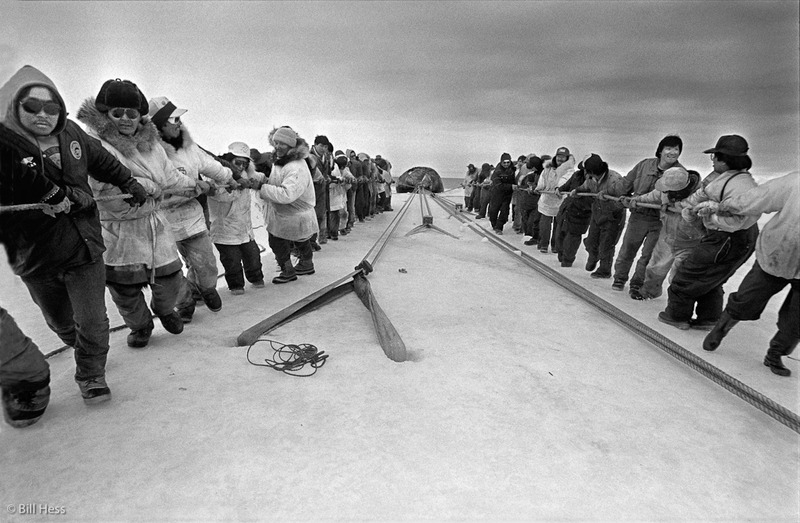

This is one of the hard lessons that he taught me. Whaling is hard work. Just to establish a camp, crews must make trails across the sea ice that can exceed 15 miles in length. They must cut their way through many pressure ridges.

I came to take pictures, but when it was time to cut through a pressure ridge, I could barely get off a frame or two before George would hand me a pick axe and order, “Put that camera down and get to work!”

This was an even harder lesson. A shard of ice can easily poke a hole through the bearded seal skins that cover the umiak, or even break the frame. To ensure that this does not happen, whalers, usually young and fit, run with the boat. Several times, we had to move camp. Each time, George ordered, “Put that camera down and run with the boat.”

I did not put the camera down, though. I kept it with me and every now and then lifted it above my bursting lungs and tried to get a frame off.

This effort would completely fall apart in the pressure ridges, where I stumbled and fell a couple of times. Once, I struggled to get back on my feet – retching, feeling like I was heaving up my guts altogether. I got no mercy from George. He stopped his machine, got off, stomped back to me, scolded me, mocked my poor “run with the boat technique” and then demonstrated how to do it right. “You are a shock absorber! A human shock absorber!”

And so I was.

It was hard. I did not want to swing a pick. I did not want to run with the boat; I wanted to take pictures, which is hard enough even when you are not swinging a pick – but, just like a young boy, I had to earn my right to be in camp. I learned things I would never have known if I had not undergone all the different tasks that George put me through.

I first went out with George in the spring of 1985, on a freelance assignment for We Alaskans, the no longer published Sunday magazine of the Anchorage Daily News. At the end of that year, I started up Uiñiq – a new pictoral magazine of life in the eight Iñupiat villages of the North Slope Borough.

I wanted to document the efforts of a single whaling captain and crew to bring in a bowhead. As George was then Mayor of the North Slope Borough. As the Borough funded Uiñiq, it seemed to me that it would be a conflict of interest if I were to focus on the Mayor’s crew. So I had to find a crew – but whose crew?

In the spring of 1986, I had no crew to follow, so I basically stayed on land but kept my ears peeled as to what was happening on the ice. When I would hear that a crew had struck and landed a whale, I would seek out a snowmachine ride and then head for the landing site. This happened two or three times, and each time the butchering process was well under way by the time I got there. There wasn’t much left for me to take pictures of.

Then, the final alloted strike of the season was made. A good lady by the name of Sally Brower let me ride on her sled and she drove me to the site where Jonathan Aiken, Sr., better known by his Iñupiaq name, Kunuk, had brought his whale. The whale was pulled out of the water even as we approached. I jumped off the sled as Kunuk climbed atop the whale with two of his tutaliks – his grandsons.

I shot this picture. I quickly ascertained that Kunuk was a quiet, humble, man – gentle and kind. I knew his was the crew I wanted to follow.

I made the request of Kunuk – that he let me follow his crew. For the next 11 months, whenever I would follow up, usually through his oldest son, Johnny Lee Aiken, the response would always be, “he’s thinking about it. We’ll let you know.”

Soon, final preparations for the spring hunt of 87 were under way. Next, I was listening to KBRW and I heard the announcment that the Aiken crew was about to give out candy at Kunuk’s house. This meant they would be going down to the ice within an hour or so.

So, feeling very depressed, I went over to get some candy and to see the crew off. Maybe, if I did so respectfully and without complaint, and then Kunuk thought about it for another year, he might take me in.

When I arrived. Kunuk and all his crew were dressed in their hunting parkas, with their bright, freshly sewn, white covers. Kunuk looked at me through dark sunglasses that gave me no hint of what was happening in his eyes.

“You coming?” he asked.

Here is Kunuk, pulling the umiak as his crew follows. I took these pictures, then scurried back to where I stayed, donned my arctic gear, hustled back to Kunuk’s house and soon caught a ride out to camp.

Kunuk’s camp, May, 1987 – waiting for a whale.

Kunuk’s crew, May, 1987 – watching as a whale moves up the lead, past another crew.

Kunuk’s crew, May, 1987 – they paddle for the whale.

Kunuk’s crew, May, 1987 – they look for the whale after it dives.

Kunuk’s crew, May, 1987 – they scrape the slush off their paddles before it hardens into solid ice. “Oh, well,” Kunuk says.

Whalers like the east wind, but not the west. The east wind keeps the pack-ice separated from the shorefast ice – it holds the lead open. The west wind blows the pack ice back to the shorefast ice and closes the lead. If a large iceberg crashes into the ice, it can shatter and break it apart. Unwary whalers can be pitched into the sea or crushed in crumbling ice.

The wind has shifted to the west. Kunuk studies the advancing ice.

Kunuk deems the advancing ice to be too dangerous. He gives the order to break down camp, pack up and head for safe ice closer to land. In about 15 – 20 minutes after I took this picture, this campsite was completely vacated.

Kunuk and crew – on their way to safe ice.

Closed lead time is a good time to hunt eider ducks, which pass by the thousands, the hundreds of thousands, the millions.

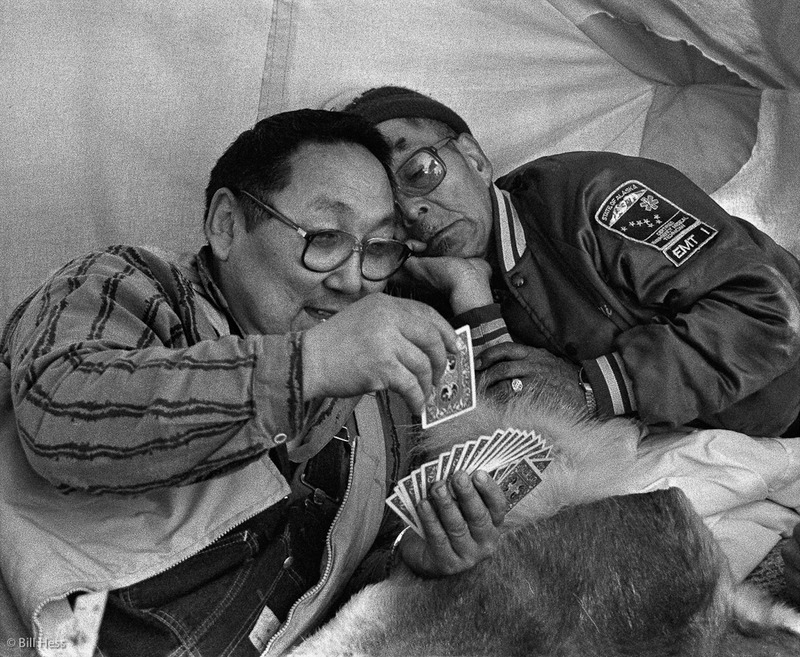

It is also a time to relax on the caribou skins in the tent, to drink coffee (I never did drink coffee until I started to hang out with whalers) tell stories, and play pinochle. Raymond Kalayuak studies his hand as Eli Solomon peers over his shoulders.

On a few different occassions that season, we would hear that another crew had received the gift of the whale. Some of the crew would go to help with the landing – I would sometimes follow, nervous that a whale might come to Kunuk while I was off taking pictures such as this.

Some might look at a whale and say, “What a giant animal – how could the people possibly consume it all? But Barrow is a big community. After helping land and cut up a whale, different members of Kunuk’s crew stood with their shares. They would get more at the feasts of Nalukatak, Thanksgiving and Christmas, but still one whale would not be even close to enough.

They needed more.

In 1977, based on information produced by scientists who did not yet know how to count bowhead whales in the Arctic, the International Whaling Commission and the US government believed the western Arctic bowhead population to number as few as 600 whales and no more than 1800. So IWC imposed a moratorium – a quota of zero – and the US agreed to enforce it.

From their own observations, the Iñupiat and other Alaska Eskimo whalers knew the government numbers to be wrong and so organized the Alaska Eskimo Whaling Commission and sent their leaders to IWC and Washington.

IWC and the US backed off a bit, but imposed a severe quota of only 12 landed whales, with no more than 18 strikes, for all ten (now 11) of Alaska’s recognized whaling villages. Barrow’s quota was four landed with no more than five strikes to land them. A decades long census effort was launched in cooperation between the US, AEWC, and the North Slope Borough. AEWC would manage the hunt, but would be under constant scrutiny. Eskimo whalers taught scientists how to better live on the ice and observe what was happening, there were aerial surverys and high-tech sound systems set up to detect and count whales that could not be seen from atop the ice or due to fog and weather condition.

In time, the census, subjected to rigorous peer review and then accepted by IWC and the US, proved that the bowhead population numbered more than 10,000 and is growing every year. The current, five-year block quota averages out to 67 strikes per year and the population continues to grow.

In 1987, the quota was still very tiny. It was not enough. Hunters had to double down on their efforts to catch caribou, seal, walrus and other animals of the Arctic – which supplement, but cannot replace, whale. Because they lead active lives in a frigid climate, they consume five to ten times the amount of flesh that other Americans do.

On April 26, 1988, the Aiken crew was the first to go down to the ice. They were soon joined by two other crews – Jacob Adams and Oliver Leavitt. I came too. We had to cut our way through a jumble of young, broken, jagged, sharded ice to get to the tenuous spot that Kunuk had chosen for our campsite.

As always, when swing a pick, I worked up a sweat. In previous years, that sweat had caused me to freeze not to death but into a state of perpetual misery. Nobody ever heard one word of complaint out of me, but I suffered. Now, I planned to sit out all day and all night for at least 24 hours and wait for a whale. I did not want to freeze. So, shortly after the tent was established, I went inside to change into dry clothes. I felt very nervous about this. What if a whale came right at the moment that I had removed my sweat-soaked clothing?

I thought about my previous three seasons on the ice. In all that time, only one whale had come within paddling distance of camp. What were the odds that one would now come in the few minutes it would take me to change into dry clothes?

I started to strip off my wet clothes, still feeling nervous. Claybo had laid down upon the caribou skins covering the tent floor to take a nap.

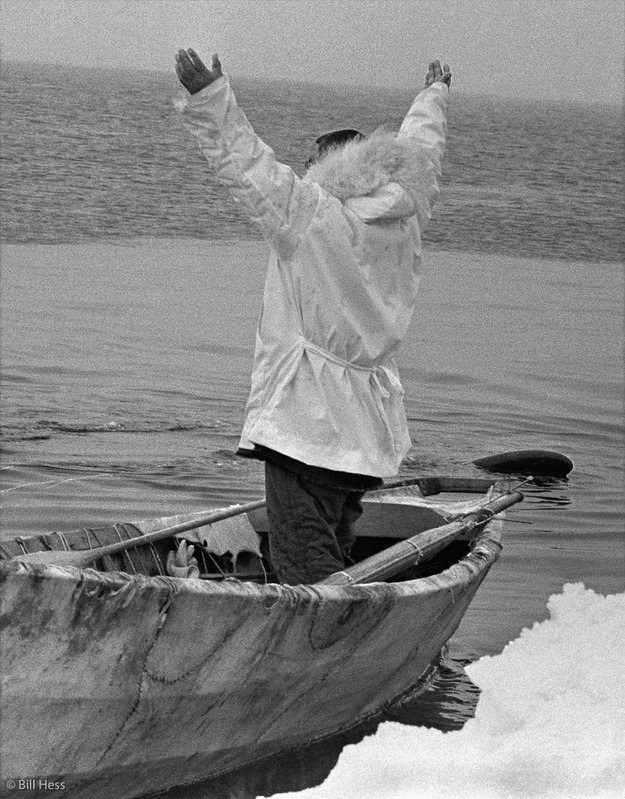

At the moment that I stripped down to my skivvies, Johnny whipped open the tent flap. “Whale!” he whispered. I jammed my feet back into my boots, didn’t worry about anything else, grabbed my cameras and slipped quietly out through the tent flap. I was surprised to see the whale RIGHT THERE, just yards in front of the tent. It had the appearance of almost bowing to to Kunuk, who had raised his harpoon. To me, it looked felt like the whale was offering itself, just as I had been taught it would.

My angle was bad. Staying crouched, I slipped maybe four feet to my right, then saw that I could not take even one more second to better my position, so I raised my camera. My breath hit the manual Canon F-1 viewfinder and froze on it, covering it with frost. I could not see through the viewfinder to focus and this was in the time of manual focus. I did not have a motor drive but only a thumb lever. I focused on instinct, fired the shutter, cranked my thumb as fast as I could.

Kunuk thrust the harpoon into the whale, triggering the darting gun that would fire a bomb. Eli Solomon followed with the shoulder gun, to fire another bomb. The whale disappeared beneath the surface. We felt the reverberations of the two bombs come up through the water and the ice. We waited…

… in just seconds, the whale rolled to the surface, flipper up. Kunuk raised his hands above his head. “Praise God!” he prayed in thanks. It was an instant kill.

Johnny and Claybo embraced. They were joyous. This whale had brought its gift to their crew. They would now have the honor of feeding the community.

Two months later, the Aiken crew joined with three other successful crews. Crew members gathered around the prepared whale, joined hands, and prayed. The feast of Nalukataq was about to begin. All who came would be fed generously. All would leave with generous portions to take home with them – as they would in the upcoming feasts at Thanksgiving and Christmas.

A blanket made from the skins of one of the successful umiaks was brought out. The first people to be tossed during breaks in the afternoon serving were children. Come night, in the time of 24 hour sunshine, the youth and adults took over the blanket.

Big Boy Neakok performed his famous flips.

In the movie Big Miracle, Malik is the captain who guides the paddling of the umiak toward the whale in the opening scene. He is a fictitious Malik, but is named for a real Malik who I have been told harpooned more bowheads in his life than any other hunter. In the movie, Malik proves to be the leading force in the whale rescue. The real life Malik would play a similar role, but with different nuance.

Tomorrow, I will introduce readers to the real Malik, together with Roy Ahmaogak, who found the three gray whales while out scouting in the hope of spotting bowheads. The three graywhales will appear in tomorrow’s post as well.

Over the past 31 years, I have been fortunate to to work as a photojournalist/writer in every region of Alaska – most extensively in the North Slope Borough, where I created and produced Uiñiq magazine, a solo photographic journal of Iñupiat life, from 1986 to ’96 - sporadically since.

I photographed and wrote Gift of the Whale: The Iñupiat Bowhead Hunt – A Sacred Tradition, including a single chapter on the 1988 gray whale rescue. I have long wanted to tell the story in more depth. Inspired by the movie, Big Miracle, I am now doing a series of rescue blog posts: