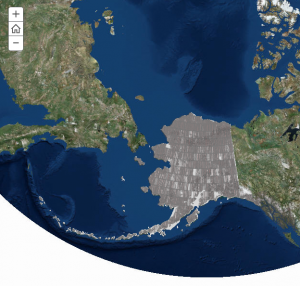

In Kotzebue a year ago, President Obama called for a publicly available high-resolution elevation map of Alaska. And today it’s here. The maps will help Alaskans monitor the effects of climate change.

There are many satellites that orbit earth. Typical satellites – like NASA’s Landsat – capture really large images, more than 100 miles across. For this project, the images are much smaller.

Paul Morin, director of the Polar Geospatial Center, says these satellites function like human eyes to help make the 3-D images.

“You can tell when things are close and far away because you have two eyes and they’re separated,” Morin said. “That’s pretty much the same principle and instead of having two satellites you have one satellite and it takes two pictures.”

Once there are two good images those pictures are fed through a super computer and software is used to find the same objects in both images. From that, it can calculate the elevation.

Morin says the elevation maps are available online and can document landscape changes.

“It can be used to look at the gain and loss of ice on a glacier, it can be used to calculate the extent of watersheds for a lake or for a river,” Morin said.

Topography on this scale is so detailed it can measure individual trees.

“We have such resolution in this data that people can go in, look at and elevation data set from say two years ago and compare it with a data set from today and you can see individual trees being cut down,” Morin said.

Collecting the imagery for this project has taken three years. Now that Alaska is completed, up next is the entire Arctic. Those maps are expected to be finished by the end of 2017.

Zoe Sobel is a reporter with Alaska's Energy Desk based in Unalaska. As a high schooler in Portland, Maine, Zoë Sobel got her first taste of public radio at NPR’s easternmost station. From there, she moved to Boston where she studied at Wellesley College and worked at WBUR, covering sports for Only A Game and the trial of convicted Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.