For over a decade, there was no place to check out a book in Kake, Alaska. Tucked into a pocket on Kupreanof Island, the Kake School District closed the library in 1999 due to funding loss. But through outside partnerships and the hard labor of volunteers, the books were put back on the shelves and the library re-opened one year ago.

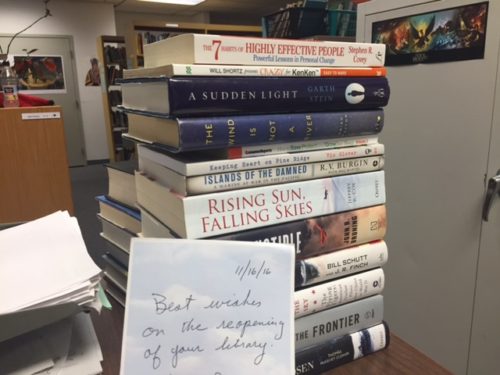

Christmas came early for Jocelyn McKinnon-Crowley. She unpacked a cardboard box, filled to the brim with hardcovers that were donated by a couple in Juneau. “Oooo, Heroes of the Frontier. Dave Eggers. These are really great,” she exclaimed, peering further into the box. On top was a note. It said, ‘Best wishes on the opening of your library,’ written in cursive on sunflower paper.

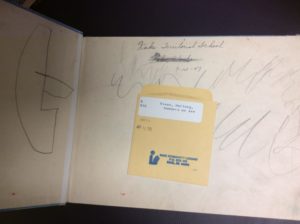

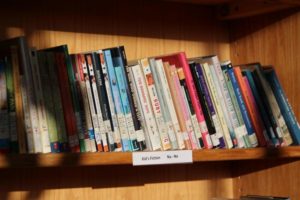

In the Shirly Jackson Community Library, named after a famed local teacher, there are bean bags, potted plants and six computers beneath a sign, which says “Light up your Imagination and Read.” The only thing out of date are the books. A good portion of the collection is pre-1999, when the library closed. And there are a lot of duplicates and classroom sets, like twenty copies of C.S. Lewis’s The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

McKinnon-Crowley is the second AmeriCorps VISTA to work on the project.

“We recently removed about 1500 kids books that were all pre-1960s kids books that were falling apart,” McKinnon-Crowley said.

To refresh the collection, the library began seeking donations of gently used books, especially those geared towards kids and about Alaska. This is the seventh box to arrive.

While the library is operated and paid for by the school district, it’s open to the public and offers programming to both kids and adults.

“Sometimes, Saturdays will be incredibly quiet and then we’ll have knitting and crocheting and it will be super quiet in here,” McKinnon-Crowley said. “And some Saturdays, six or seven kids will show up.”

Kevin Shipley is the Superintendent and Principal of Kake’s schools. Re-opening the library has been a major goal of school administration.

“Watching the kids have an opportunity to say, ‘Hey, I can actually have a place to learn and use,” it’s a great thing,” Shipley said.

And, as Shipley explained, the resurrection of the library mirrors the history of Kake.

In the 1990s, Kake’s economy – built on logging and fishing – collapsed from what Shipley calls a “perfect storm of factors.”

“You had the [federal government] put regulations on logging, you had changes in the fishing program and then you had prices of fuel go up,” Shipley said.

School enrollment dropped as families left, which cut funding. And the library was one of the casualties.

“You cut the fat first, then you cut muscle, then you get down into the bone. So we are bare bones here,” Shipley said.

When Shipley arrived in 2012, most of the collection was packed in boxes. But that year, the school had a lucky break. Enrollment was 101 and that extra student qualified them for $300,000 through the state’s per-pupil funding formula.

With the extra cash, Shipley hired a principal, Evelyn Wilburn who, alongside community member Marsha Ward, got the library back on its feet. The one-year anniversary of the reopening was in October. Over fish spread and pumpkin bread, the library gave out books for free. But there’s a new problem now: with new books coming in, what happens to the old books?

Jori Grant is the Kake High School’s English Teacher. She and McKinnon-Crowley, the VISTA volunteer, are roommates. They have to drive down one of Kake’s old logging roads to get to the town dump, which is the end of the road for all of Kake’s trash.

Barging trash off the island is too expensive. So effectively, every book that comes to Kake has to stay or be set on fire in the town dump. Grant said this has been a bit of a sore spot as the library tosses outdated books, a process known as “weeding.”

Grant remembers setting out a box of books once.

“The box broke open and people were like, ‘[The library] is throwing away the books!’,” Grant said. “But we’re like, ‘Guys, these are really bad old books. We can’t afford to send them other places, so what else are we going to do with them?’ But it’s still ingrained to not burn books that everyone is very against it

For some, it’s not easy to watch even old books burn. But McKinnon-Crowley explained that that libraries aren’t archives. They have to change with the times. Right now, the library sees about 40 visitors per week. And the best way, she said, to get that number up is by giving readers the books they’re looking for.