Exactly 150 years ago, on March 30, 1867, the United States signed a treaty to buy Alaska from Russia. The treaty changed the course of Alaska history, but did it leave any mark on the city where it was signed?

These days, the concept of “buying” Alaska seems to call for quotation marks, since many Alaska Natives dispute their homeland was owned by either country. Maybe it’s more accurate to say the U.S. bought “Russia’s claim” on the land.

None of this troubled William Henry Seward, the man with the foresight to “buy” Russia’s piece of America. He served as secretary of State a full eight years, under two presidents, but of all the national monuments in Washington, D.C., none is devoted to Seward. No plaque or statue marks the spot where Seward signed the purchase treaty with Russia.

A few miles away, near the U.S. Capitol, there is a “Seward Square.” But it’s not even a real square. It’s criss-crossed by eight lanes of traffic, creating a collection of grassy patches.

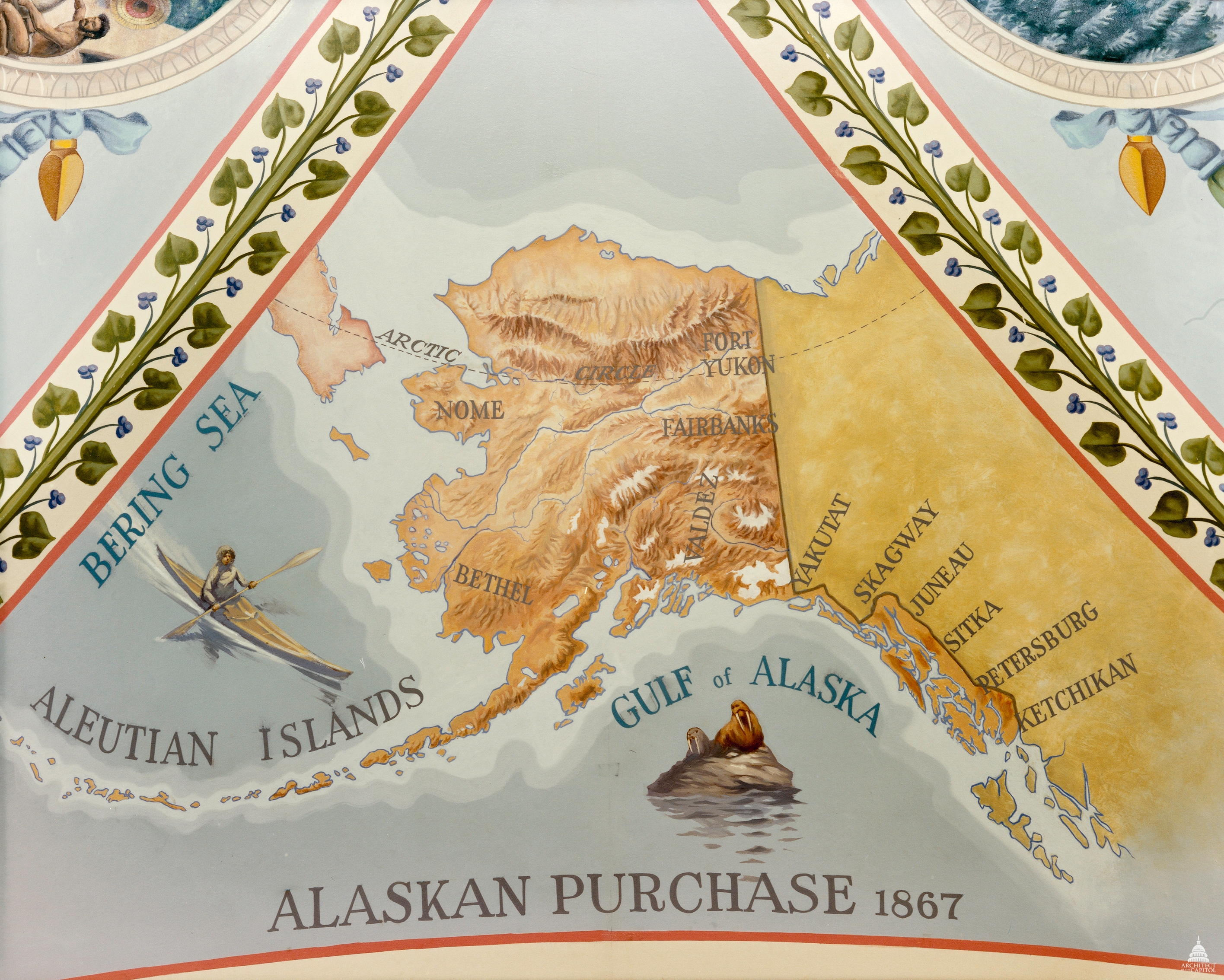

A better tribute to Seward’s accomplishment is inside the Capitol, down a hallway that doesn’t see many tourists. It’s all the way to the end, next to an elevator. Painted on a vaulted ceiling is an artist’s rendition of a map of Alaska and the words “Alaska Purchase 1867.”

It turns out there’s a reason this mural is at the very end of the hallway.

“I would describe it as a ‘figurative style,'”Architect of the Capitol Curator Michele Cohen said. She said artist Jeffrey Greene was working within constraints.

“He’s trying to be very consistent with the style that defines Allyn Cox, which would be called sort of an academic, figurative style,” Cohen said.

Allyn Cox was the artist first hired to decorate this side of the Capitol. He planned a series of murals depicting the nation’s history, and he designed them to fit in with the 19th century murals elsewhere in the building. The Cox murals look something like old botanical illustrations, or Audubon prints, but showing people and places rather than plants and birds.

It was Cox who conceived of the “Westward Expansion Corridor.” Cohen points out that the murals are chronological: Exploration, Daniel Boone, the Louisiana Purchase, etc. And at the very end, the acquisitions of Alaska and Hawaii.

Cox, though, died before he could paint “Westward Expansion.” Years later, Greene took the project on. Only by then, it was the 1990s and ideas about Western Expansion and “manifest destiny” had evolved. Cohen says Greene wanted his work to reflect the understanding that the West wasn’t empty land before the settlers arrived.

“He thought about the iconography and the content that was part of the original design and he wanted to make it a more inclusive mural, and a more nuanced historical narrative about Westward Expansion,” Cohen said.

It’s subtle, but it’s there: Greene painted Lewis and Clark gazing out over a Native American village, rather than untrammeled wilderness. For Alaska, Greene added a person in a kayak to the map. (Not to scale, of course. The guy’s boat is nearly as long as the Aleutian Chain.) Greene also included the names of Alaska towns and cities.

As the curator sees it, that’s how the artist met the challenge of honoring 19th century concepts from a modern perspective.

Happy Alaska “Purchase” Day.

Liz Ruskin is the Washington, D.C., correspondent at Alaska Public Media. Reach her at lruskin@alaskapublic.org. Read more about Liz here.