The Solutions Desk looks beyond Alaska’s problems and reports on its solutions – the people and programs working to make Alaska communities stronger. Listen to more solutions journalism stories and conversations, and share your own ideas here.

If someone breaks their arm or twists an ankle, we generally know what to do – brace it and get help. But what if someone is hurting mentally instead of physically? A bandage won’t help, but a Mental Health First Aid class will.

Two women sit in a classroom, role-playing what it would be like to be on a turbulent airplane when a person experiences a panic attack.

“Ugh,” moans one woman as classmates rattle the furniture making noises.

“Hey. Are you ok? Can I do anything to help?” asks Amber Etageak. “Can you just relax and try to breathe? Take a deep breath.”

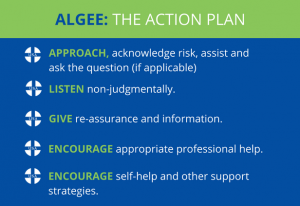

Etageak listens to the woman’s concerns and tries to reassure her. She suggests slow breathing and thinking of happy thoughts. Listening without judgment, giving reassurance, and encouraging self-help strategies — those are some of the main skills taught in Mental Health First Aid classes around the world. And they work.

“Ok, so this short little flight and then we’ll get there and everything will be ok,” Etageak says reassuringly as the role-playing ends. “We’re gonna be alright.”

“I think so,” agrees the woman, a bit calmer. “I’m breathing better. Thank you.”

Even though it was just a role-playing exercise in a safe space, and even though Etageak has been around people who were having mental health crises before, she says it was scary.

“It was an intense situation, I mean because things like that could really happen,” Etageak says. “I wasn’t sure if it was going to get out of hand or it was going to get physical. And you never know.”

Part of the idea behind Mental Health First Aid is to train people to respond appropriately to help another person when situations are tense. The class helps people assist with short-term mental health crises – like a panic attack on a plane, or suicidal thoughts – and to broach longer-term issues, like depression or substance abuse.

“The context (for using the skills) ranges from one’s own family to work situations to even strangers on the street,” says Jill Ramsey, the behavioral health training coordinator for University of Alaska Anchorage. She has been teaching the class for more than 6 years.

Just like CPR, Mental Health First Aid focuses on a series of steps. Assess the risks – is the person thinking of hurting themselves or others? Listen to the person and hear what their concerns are and give them reassurance if they need it. And then help them connect with resources. She says the class teaches necessary skills for a first response, not a long-term intervention.

Just like CPR, Mental Health First Aid focuses on a series of steps. Assess the risks – is the person thinking of hurting themselves or others? Listen to the person and hear what their concerns are and give them reassurance if they need it. And then help them connect with resources. She says the class teaches necessary skills for a first response, not a long-term intervention.

“We really don’t want people diagnosing other people,” Ramsey says. “We don’t want people out there trying to be therapists. We really want people to be doing first aid.”

The 8-hour-long course was developed in Australia in 2001 and is now taught around the world, including Pakistan, Denmark, and Saudi Arabia. It teaches the signs and symptoms associated with major illnesses like depression, anxiety, and substance abuse as well as the appropriate way to respond.

Research shows participants develop, maintain and use their new knowledge over time. The program also reduces the stigma around mental illness.

About one in five people in the United States has a mental illness. Ramsey says awareness of the illnesses and their prevalence changes how people interact and respond.

“Most of the things that we’re seeing are brain disorders,” she explains. “They’re not character flaws. They’re not moral failures. These are real illnesses that deserve attention and compassion.”

There aren’t any studies with people who have received mental health first aid – it’s hard to track those folks down. But anecdotally, the methods are effective.

There aren’t any studies with people who have received mental health first aid – it’s hard to track those folks down. But anecdotally, the methods are effective.

Ruth Adolf is an officer with the Anchorage Police Department and helps teach the course to other officers and to the general public. She says people who interact with officers who have mental health first aid training are calmer and more responsive because the officers listen with a greater awareness.

“It’s very important to understand when you go into a situation what you’re dealing with,” Adolf says. “And you can easily learn that by being patient, by taking your time, by learning from that person what’s going on. Not always easy but it’s necessary. It’s valuable.”

The class is now part of the police training academy in Anchorage. It’s also taught to health care professionals and the general public. A youth-specific version is available, too.

Want to hear more Solutions Desk stories? Subscribe to the podcast on iTunes, Stitcher, Google Play, or NPR.

After being told innumerable times that maybe she asked too many questions, Anne Hillman decided to pursue a career in journalism. She's reported from around Alaska since 2007 and briefly worked as a community radio journalism trainer in rural South Sudan.

ahillman (at) alaskapublic (dot) org | 907.550.8447 | About Anne