Congress has voted to allow oil development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, but drilling opponents haven’t given up. As part of their strategy going forward, they’re looking beyond Washington, D.C. and across the U.S.-Canada border for support.

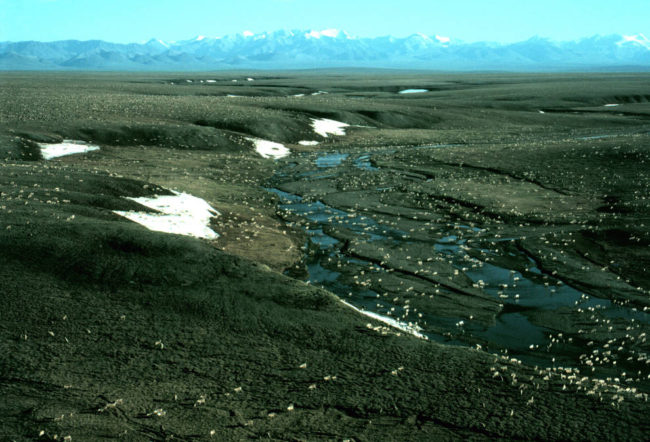

Canada has a long history of opposing oil development in ANWR. That opposition comes down to the caribou.

“If there is development in this area and when we do lose the caribou, that will be a significant channel of life that will have dried up and shut down forever,” Dana Tizya-Tramm, a Vuntut Gwitchin council member in Canada’s Yukon Territory, said. “My people will remember the death of the caribou and the death of this area for thousands of years.”

The Porcupine Caribou Herd migrates into Canada and is hunted by the Gwitchin who live there. Like the Gwich’in in Alaska, Tizya-Tramm believes any disturbance of the herd’s calving grounds in the refuge is a threat to his community.

This is not a new issue. In 1987, the United States signed a treaty with Canada, requiring both countries to “avoid or minimize activities” that would disrupt the Porcupine Caribou Herd. Now, as the Trump administration pursues oil development in the Refuge, Tizya-Tramm said the agreement means the U.S. is obligated to consult with Canada before it drills there.

“We really have a legitimate voice here…that belongs in this issue,” Tizya-Tramm said.

Canada’s leadership agrees — its position is that the Porcupine Caribou Herd’s habitat should be permanently protected. In an emailed statement, Colin Shonk, a spokesperson for the Canadian Embassy, said, “the federal, territorial and Indigenous governments in Canada are united in their commitment to conservation of the herd and its habitat.”

“We remain committed to the implementation of the 1987 Agreement between Canada and the U.S. to protect the herd,” Shonk said.

Environmental groups in the U.S. see the treaty as a way to stall the push for oil development in the refuge.

“Certainly the Canadians have made it clear that they expect the treaty to be observed and implemented,” Mike Anderson, a lawyer with the Wilderness Society in Seattle, said. “This is not what necessarily the Trump administration wants, in terms of their rushed timeline.”

Anderson said if the U.S. abides by the treaty, it will have to take a careful look at potential impacts on the Porcupine Herd. And that, he hopes, will spur Congress to reconsider whether drilling should be allowed. But Anderson acknowledges the treaty has limits — he said the final decision will be up to the U.S.

Jutta Brunnée, a professor and an expert in international environmental law with the University of Toronto, agrees. Brunnée says the agreement is legally binding, and its strength lies in the requirement for the U.S. to “promptly” consult with Canada if the herd is significantly harmed.

Canada is entitled to consultation, but “that’s, I think, as far as we can take it,” Brunnée said. “There is no commitment that either side makes that they would stop development.”

That said, American supporters of oil development in ANWR are not unconcerned about Canadian interference. To the dismay of Alaska’s congressional delegation, Canadian representatives in Washington, D.C., lobbied against the provision in last year’s Tax Bill that opened up the refuge to drilling. Senator Dan Sullivan said, in response, he called the Canadian ambassador for what he referred to as “a very frank discussion.”

“And the first thing I said was, ‘Ambassador, I’m not sure you understand what your own country’s interests are,’” Sullivan said.

Sullivan said he told the Canadian Ambassador that Alaska’s congressional delegation is “the most pro-Canada delegation in Congress.” Then, Sullivan said, he told the Canadian ambassador to cease and desist the lobbying campaign.

In later meetings with Canadian officials, Sullivan said he passed along this message:

“We’re of course going to work with Canada, but this kind of action undermines your own country’s interest. Because we’re going to remember it,” Sullivan said.

True to his word, Sullivan said he’s preparing to introduce a bill related to the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund — a fund that oil producers must pay in to, used to cover the cost of oil spill cleanups.

“And there was always a glitch — always…in some ways, a loophole, that Canadian tar sands that comes across the border into the United States, produced in Alberta, has never had to pay that fee,” Sullivan said. “Well, I think we should close that loophole.”

Asked if the bill will be in direct response to Canada’s lobbying actions last year, Sullivan said the move was under consideration before Canada opposed the ANWR provision.

But, the Senator added, “let’s just put it — we were thinking about it. We hadn’t made a final decision. And their actions certainly helped us make the final decision.”

Like many proponents of drilling in ANWR, Sullivan said he believes the Porcupine Caribou Herd can stay healthy alongside oil development, if it’s done responsibly.

But Sullivan also didn’t dismiss the fact that the U.S. has an obligation to uphold the 1987 treaty. So Canada could ultimately take its seat at the table — but whether it can convince the U.S. to stop oil development in ANWR is a much taller order.

Elizabeth Harball is a reporter with Alaska's Energy Desk, covering Alaska’s oil and gas industry and environmental policy. She is a contributor to the Energy Desk’s Midnight Oil podcast series. Before moving to Alaska in 2016, Harball worked at E&E News in Washington, D.C., where she covered federal and state climate change policy. Originally from Kalispell, Montana, Harball is a graduate of Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism.