Climate change may have spurred the first humans to move into Interior Alaska. A new University of Alaska-Fairbanks study, released on Tuesday, found that around 15,000 years ago, the Bering Land Bridge became much wetter and warmer. That coincides with when people began to leave it.

Mat Wooller is a professor in the college of fisheries and ocean science at UAF, and the study’s lead author.

“For anyone who has lived in Alaska and even been up onto the North Slope, you know that that environment is very tough to…move around in with wet kind of conditions,” Wooller said. “So that might’ve prompted people to move out of that, that environment into a more favorable landscape.”

Wooler said that as the already wet climate of the low-lying Bridge changed, that may have also increased the mosquito population, pushing caribou and the people that hunted them away from mosquitoes and into the interior.

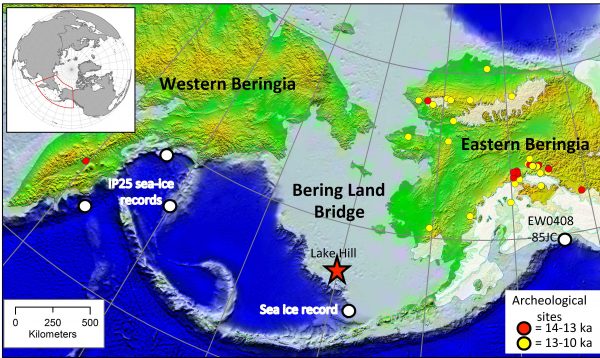

“The Bering Land Bridge, which is where humans were coming across from Asia into North America, is now flooded. But at one time, of course, it was connected,” Wooller said. “And the site that we chose, St. Paul Island, has been exposed and part of that Bering Land Bridge all the way back at least 18,000 years ago.”

Over the course of years, a team of international researchers studied a long core of sediment pulled from a lake bottom on the island. They were initially studying the environment before, during and after mammoths went extinct on the island but had leftover sediment and decided to expand their research.

From that, they created an 18,500-year timeline of temperature and precipitation patterns. They also studied fossils found in the sediment from bugs, plants and spores.

“When those organisms change and the species change, that tells you how the environment changed and you have this timeline constructed and you can see how the climate changed over time,” Wooler said.

There’s a lot of debate and questions about how exactly the earliest humans made their way to North America, and Wooller said the study helps fill in those gaps with empirical data. And the data can be used to help improve climate models. The better researchers understand how the Arctic’s climate has changed over time, the better they can predict how it might change in the future.

Erin McKinstry is Alaska Public Media's 2018 summer intern. She has an M.A. from the University of Missouri's School of Journalism and a B.A. from Knox College. She's reported stories for The Trace, The Midwest Center for Investigative Reporting, Harvest Public Media, the IRE Radio Podcast, KBIA and The Columbia Missourian.