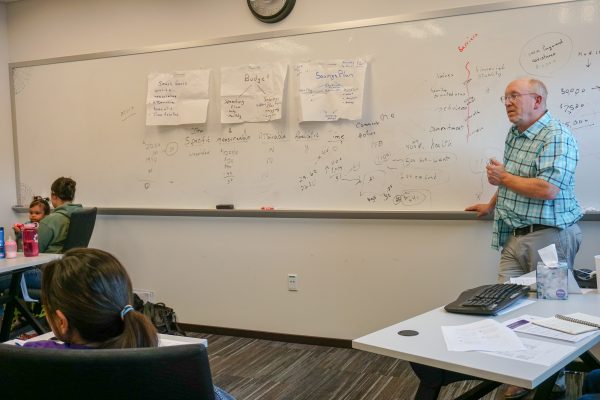

About a dozen people, including a baby, sit in a classroom at the Knik Tribal Council office in Palmer discussing building a budget and putting aside money each month. They share ideas about ways to spend less on food and phone apps that offer good deals. After the two hour-long class, participants stay to talk to the teacher and Ayumin Moses reflects on what she learned.

“This class is really exciting,” she said. “And it’s really, really opened my eyes and helped me realize the things I need to do to make positive changes for me and my girls.”

Moses recently separated from her husband, and her financial situation is drastically different than it used to be, she said. She knows she needs to be financially stable before reaching for one of her biggest goals.

“I eventually want to own my house,” she said. “That’s one of my goals. That’s one of the things I have on my wall. I made a list of what I want in my life.”

But with a poor credit history, it could be a while before Moses could get a loan from a traditional bank. Instead, she can now turn to Knik Tribe’s Community Development Financial Institution – or CDFI. It’s like a bank with a mission to help the community, and it relies on relationships.

“Instead of lending money to what the numbers are, [CDFIs] lend money to the person,” explained Richard Porter, the Executive Director of the Knik Tribal Council.

This flexible financial organization has a pool of money from government, private, and non-profit sources that can be lent to people who wouldn’t be eligible for a traditional loan or who would get really high interest rates. The whole point of the program is to offer financial opportunities in low-income communities.

“When you try to go to go get a loan and your credit is bad, well guess what? You pay 20, 25 percent on the dollar,” Porter said. “Well how does that work out? Does that help you get ahead, to move forward in your financial situation where you can actually begin to create wealth after home ownership?”

Knik Tribal Council started developing it’s lending program three years ago and is just now giving out housing loans. They are the only statewide organization of its type, though there are other regionally focused ones. At least half of their clients need to be Alaska Native or American Indian, but anyone can apply.

Porter said one of their primary goals is to make it possible for people to keep living and working in rural areas instead of migrating to the Mat Su Borough. “They end up here, and they end up costing our system a lot of money if they don’t want to be here,” he said. “So we’re interested in, if they want to stay out in the village, that we can help them accomplish that.”

One regional financing group has already shown that the flexible community development tool is an effective solution for rural Alaska, where traditional banks don’t often have branches. Spruce Root started in southeast Alaska six years ago. Business Development Director Paul Hackenmueller said that so far, they’ve only given out a dozen loans totaling about $800,000, though the number of proposals is growing.

But Hackenmueller said success isn’t just measured by the number of loans. As the name says, a CDFI is aimed at community development, which means developing long-term capacity.

At Spruce Root, they work with entrepreneurs in seven small Southeast communities to develop business plans. After going through the process, some of their clients realize they can start their businesses without any help. Others figure out they shouldn’t even bother trying for a loan.

“Sometimes we work with an entrepreneur and they realize, ‘Wait a minute, this business will never make me money. So I’m going to stop today, after going through this business planning process, and not spend the next two or three years of my life and who knows how many thousands of dollars, trying to run a business that will cost me money every time I open the door,'” he said.

“Sometimes we work with an entrepreneur and they realize, ‘Wait a minute, this business will never make me money. So I’m going to stop today, after going through this business planning process, and not spend the next two or three years of my life and who knows how many thousands of dollars, trying to run a business that will cost me money every time I open the door,'” he said.

Ultimately, Spruce Root’s goal is similar to Knik Tribe’s goal – to help people thrive in their home communities and not have to relocate.

“The focus has always been on strengthening rural economies here so that the people who live here now and have lived here for thousands of years can continue to do so,” Hackenmueller said.

Both Spruce Root and Knik Tribe think offering a flexible financial tool that depends on relationships instead of numbers helps level the economic playing field so that people can do just that.

After being told innumerable times that maybe she asked too many questions, Anne Hillman decided to pursue a career in journalism. She's reported from around Alaska since 2007 and briefly worked as a community radio journalism trainer in rural South Sudan.

ahillman (at) alaskapublic (dot) org | 907.550.8447 | About Anne