Every official ballot cast in Alaska this election will be printed in English. But for voters whose primary language isn’t English, they will likely find assistance in a familiar tongue.

“This work addresses deficiencies in the democratic process that have gone back for a whole generation or two in which Alaska Native voters were really disenfranchised,” said Indra Arriaga, who is the elections language assistance compliance manager at the Alaska Division of Elections.

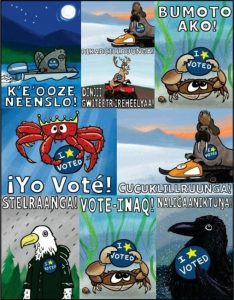

Arriaga heads the state’s program to translate elections materials. Right now there are 10 full ballot translations available: eight Alaska Native languages and dialects, as well as Spanish and Tagalog. For historically unwritten languages, the state provides oral assistance, most often recordings.

Voters can use the translations side-by-side with the official ballot — the one that gets counted — reading or listening to translations of each section, then marking their choices on the English version.

Arriaga doesn’t write the translations: She oversees translation panels. Made up of fluent speakers, most of them elders, these panels pick apart dense elections materials, line by line.

“These are complicated measures that have huge impacts on the everyday lives of people. When you read a ballot, it’s usually so complicated that it’s very difficult to understand, even in English.”

The panels take that jargon and break it down. They want their translations to make sense to voters in their rural, majority Alaska Native communities. That means explaining concepts like like “the good old boy network,” or even “candidate.”

Arriaga said the translations are typically much longer than the English original and added, “I think that actually the translations that we do in Alaska Native languages, and this is simply my gut feeling, is the translations are probably better.”

That matters, especially for Alaskans without much access to lawmakers.

Arriaga recalled working this summer in New Stuyahok, a Yup’ik village of about 500 near Dillingham. Their task: to translate Ballot Measure One. That’s the controversial initiative that would beef up protections for Alaska’s salmon habitat.

Like many villages in the state, New Stuyahok relies on the salmon fishery for both subsistence and income.

“So there are a lot of emotions that are attached to it, regardless of where they stand on it,” Arriaga said.

That could be a problem.

“My job then is to work with them, so that even though they may have concerns we have to translate what is there. And that is where working with a panel is really important.”

The panel members help each other find the right words and hold everyone accountable, keeping out personal opinions and biases.

Arriaga sees the project as a piece of something much bigger. For all Alaskans.

“I want them to understand how important it is for Alaska. It helps everybody. You don’t have to be Alaska Native to support this. You don’t have to be a speaker of any language to support this, because the benefits of diversity and the benefits of a multilingual society is huge.”

Alaska voters who need language assistance on election day can call 866-954-8683 between 7 a.m. and 8 p.m. to speak to a translator.