Traveling east towards the Chugach mountains near Anchorage, it’s hard not to notice a large dirt road winding up the mountains in what otherwise is an untouched mountainous wilderness.

What is it?

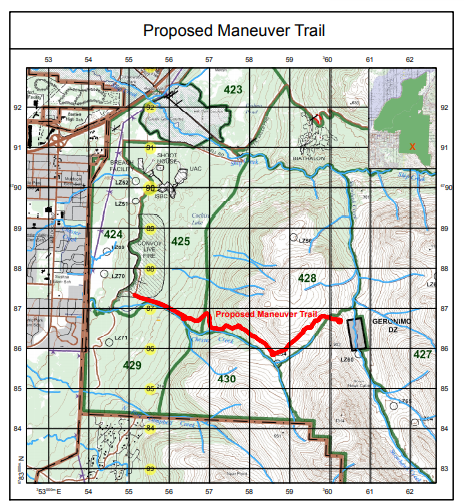

An emergency access trail in JBER territory to allow firefighting equipment to access an area near Kanchee and Knoya peaks, according to JBER officials. They say the 4-mile trail is needed to respond to potential wildfires as training with live ammunition in the area can cause fires.

But some neighbors are feeling a little misled.

Karen Bronga lives in East Anchorage and has been using JBER’s trails for decades. She’s part of the community council and remembers a presentation back in 2016 about the trail project.

“We just all listened and nodded and felt pretty okay with it. And I still think a lot of the community is okay with it. But the thing is, it was kind of represented as a trail,” she said.

Plans for the trail call for a 60-foot wide clearing through the four miles of trail, which winds up to a mountain pass above the North Fork of Chester Creek, then over to Snowhawk Valley. The trail itself takes up 30 feet of that clearing and is covered in 2 feet of gravel. To Bronga, that sounds like a road.

Mark Prieksat is the deputy commander for the 673rd Engineering Squadron and has worked on the project since its inception in 2014. So what is the difference between a “road” and a “trail”? Prieksat says the corridor is called a trail because of the surface of it: it’s gravel not asphalt.

“You can get larger fire and emergency service vehicles into that area. But you also want something that’s going to last and endure and you don’t want something that’s just going to erode away like a mud road,” he said.

Prieksat says that the training area located at the end of the trail, called the Geronimo Drop Zone, has been used for years to drop paratroopers for training. But about five years ago, an environmental analysis highlighted that unlike other areas on base, there was no ground access for emergency vehicles in the area. That meant that for both accidental and prescribed burns, there was no easy way to get there.

“It’s always been a point of contention because there’s no real access to that area. And even though you can get there with a helicopter with drop buckets, you can’t get people and equipment in there effectively,” he said.

And, he said, its width can also serve as a fire break, though that is a secondary purpose.

The area has been closed for public access recently, but many hikers and skiers are still hopeful that the area will eventually be reopened after construction is complete. Bronga says she skied up the trail last year, before it had been widened and graveled.

“It has created some pretty incredible access to the mountains. And the views, when you turn around and come back of the city, are amazing. It just would be a lot nicer for me if it were a trail going up there,” she said.

Those views are only as good as the time that the area is open. Unlike the adjacent Chugach State Park, JBER requires a permit for access – even walking. Users also have to register each time they enter through an online portal or in person on base, which can require planning and internet access. There’s also a good chance that the units can shut down so that the military can conduct live ammunition training exercises. In recent years, blocked access throughout the summer has even led Scenic Foothills Community Council to demand more openings by the base, something that eventually was eventually accommodated.

Prieksat highlighted the trail was not designed for recreational access, and JBER officials haven’t made indications of whether or not it might be allowed. Prieksat said that decisions about opening are made between the Range Control and some other officials on base.

“I think that’s a decision yet to be made,” he said referring to reopening the units in that area, “I think the one thing that we don’t want are people accessing that doing overnight, having campfires up in those areas.”

In any case, overnight camping and the use of campfires isn’t allowed, even with a recreational use permit, though Preksat says that there have been many trespassers in recent years.

Stu Grenier, another East Anchorage resident and longtime recreational user of the area, says that it’s hard to predict what access to the training areas will be like on a daily or yearly basis, which can be frustrating. But he says that over the last decades, access has tended towards more restrictions.

“When I was a kid, it was no big thing to take motorcycles right up over the top of the Dome, which is now called the Dome, then it was called Motorcycle Mountain,” he said.

But while that sort of easy, free access is a thing of the past, the Grenier says a bigger factor is who’s in charge of the base. One year, the commander might be amenable to opening the base as much as possible for recreational users. The next it might be someone without any interest – or even understanding of keeping the base open for public recreation.

“One of the things that we learned is, inconsistency is not unexpected with the base,” he said.

Grenier says he isn’t at all surprised about the new trail that was built. As part of the Northeast Community Council, JBER officials presented on the project. He also brought that information to a Mountaineering Club of Alaska to get the word out to the outdoor community.

He said that he, as well as the community council, actually supported the project, not that they had any real voice in whether it was built – it is the United States Army, after all. But supporting the project was at least partially out of self-interest, he says: while he can’t control who the unit commander is at JBER, Scenic Foothills and Northeast Community Councils have been working on securing some of the JBER land for unrestricted public use by building a bike trail from the Glenn Highway to Chester Creek.

To do that effectively though, Grenier says the city would need to acquire JBER land a little farther from the current 20-foot easement along the military fence. He says part of the reason he’s supported JBER emergency access trail is to gain some goodwill for that land swap.

“I was grateful that they took the time to send a public affairs officer and inform the community. But it does clearly expand their usable range, especially with their vehicles. And maybe that could be part of the argument why we could use a little bit more land,” he said.

But that might be years, or even decades away. Bronga says in the meantime, she’s expecting many more years of fighting for public access for the trails she’s used since childhood.

“I just don’t see it changing, I really don’t,” she said.

This story has been changed to make clear that JBER is a military reserve, not a park and to correct information about the trails purpose as a firebreak that was included in an environmental analysis.

Lex Treinen is covering the state Legislature for Alaska Public Media. Reach him at ltreinen@gmail.com.