Just a couple of months ago, 39-year-old Moses Aguilar was living in a cot on the floor of the Sullivan Arena. Now he’s fully employed and about to move into an apartment with his own room.

“From a cot to a palace,” he joked.

As winter approaches, Anchorage homeless advocates are racing to get people who are in the city’s shelter, one of the nation’s largest, into housing.

That included Aguilar, a recovering addict who has spent many years in jail. But by his own telling, his story of getting his own place involves a series of miracles.

Advocates agree that many don’t have it so easy though they are making progress.

“There are so many opportunities to not get it right, and so few opportunities to get out,” said Katelyn Sheehan, who oversees resources at the shelter.

Providers have found some success: 260 people have moved through the Sullivan Shelter into more stable housing, according to managers there. But many more don’t make it out because of things like mental health issues, stigma that makes it hard to find jobs and bureaucratic hang-ups.

Like many who go through the shelter system, Aguilar’s story started with a rough upbringing. Born in Texas, his parents passed away when he was young. He turned to drugs as as a way to cope with the loss.

“I started doing meth when I was 12 years old, and I started drinking,” he said.

Despite a supportive aunt who took him in, he continued to have run-ins with the law and couldn’t break his addiction. He spent time in jail: A total of 17 years in five different prisons, he said. Eventually, he said, something drew him to Alaska. He lived in Fairbanks, worked at McDonald’s, and then moved to Northway, pulled in by a relationship he called “abusive.”

One day, something changed inside him and he left, carrying just a backpack, he said.

He stuck his thumb out on the Alaska Highway and seven hours later got dropped off at the Sullivan Arena.

Immediately, he said, a friend from Fairbanks recognized him and approached him in the parking lot.

“They had some meth, and they wanted for me to go back into the darkness with him and get high with him. And I said, ‘You know what? I don’t do that anymore.’ And I was firm in that,” he said. “God broke the chain that had bounded to me for so many years.”

But breaking the addiction was just the first step on his journey out of homelessness. The next hurdle was bureaucracy.

To apply for social programs and move towards permanent housing, he needed identification. That’s where, he said, he ran into his next problem.

For most housed people, losing an ID might mean having to show a passport or birth certificate at the DMV to prove your identity. Aguilar had none of those, which pushed him into a Kafka-esque problem of having to prove he was who he was.

“I had no identification card. I had no birth certificate. And I had no security card. I had no credentials whatsoever,” he said.

With $36 in his pocket that a church gave him and without another penny, he said, he sent in a request for a birth certificate from Odessa, Texas, where he was born.

“So instead of spending that money on anything else, especially my energy drinks I love so much, I spent it on my birth certificate,” he said.

But without a permanent address, he wasn’t allowed to receive the birth certificate without a photo identification, so Aguilar found himself at another dead end, he said. It’s a common problem for people moving out of homelessness, said Colby Bleicher, a navigator at Bean’s Cafe who helps connect people to the services they need.

“I’d say we get at least 30 requests for identification vouchers every week, we see a lot of folks who have had their IDs or their whole wallets stolen,” she said.

It’s especially hard for people who have moved from different states, since whatever official documentation they have is scattered through different agencies, she said.

For Aguilar, a string of good luck continued and a navigator found an unexpired ID through the California shelter system.

At the same time, Aguilar was moving up through a pipeline from Bean’s volunteer to employee. After helping in the kitchen for several weeks, he caught the eye of Aaron Lochridge, a shelter manager who runs a program called Shelter to Success.

“Moses pretty much did everything,” Lochridge said. “He was just a stellar volunteer all the way around. And he’s a stellar guy. And he came around, and quite a few people recommended him to me.”

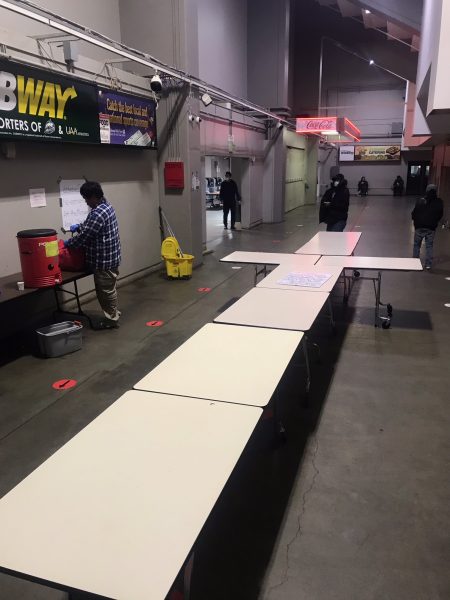

That led to a job offer as a paid employee of Bean’s working in the kitchen. For his work, Aguilar recruits volunteers from the cots on the floor of the Sullivan and oversees the production of several hundred sandwiches, which are served to clients at the shelter. Later in the day, he sets up a concession stand using lunch tables pushed into the shape of a cross. He gives out prepackaged meals for free. He calls it “The Lord’s Concession.”’

He also moved out of the shelter and into a halfway house nearby. It was a life-changing opportunity, he said, and he was one of just nine who were offered employment with Shelter to Success. And even for the most promising recruits, getting a paycheck was a double-edged sword.

“We’ve had people that basically didn’t set all the right things until they got that first paycheck, and then went back to their old habits,” said Lochridge.

Lochridge said that he’s trying to develop partnerships with other organizations who can help people stay on track through budgeting workshops and help with drug addiction. But as always, funding and personnel are hard to come by.

Moving on

Aguilar had the day off work on Monday, and used it to shuttle around to different appointments. A volunteer from New Hope Ministries was chauffeuring him for the day, starting out at Cook Inlet Tribal Council. As a member of the Cherokee Nation, Aguilar is eligible for federal programs for subsidized housing, which he’s hoping to move into soon.

Later in the day, he’s scheduled to get tours of a few apartments, and he hopes to move into a place with a room of his own soon.

He said he’s also looking to become self-sufficient to get around town, so his next stop was the DMV.

“Humiliatingly, I’m getting ready to pick up my permit at 39 years old to be able to drive for the first time as a licensed driver,” he said, as he waited to be called up for his appointment.

Aguilar passed the test, and spent the rest of the day practicing driving in the vehicle of the ministry volunteer.

For him, it’s one more lucky break on the narrow path out of homelessness. He said knows he’s lucky. Sheehan, the resource hub director, said that his story is unfortunately an exception.

“You have to get every single thing lined up perfectly at one time, in order to be able to really progress,” she said.

Along the way, opportunities are so rare, and people like Aguilar have to be in the right place emotionally and psychologically to cache in on them. Passing through one bureaucratic hurdle might mean weeks of waiting for the next appointment at the DMV. In the meantime, people experiencing homelessness are susceptible to lapse back into bad habits that brought them there.

“Having someone wait eight weeks to get in to have their ID doesn’t enable them to become employed, which therefore doesn’t enable them to elevate themselves out of poverty,” said Sheehan.

The resource hub at the Sullivan has been a huge help for clients at the shelter. Navigators can help set up appointments at a myriad of agencies in Anchorage, help coordinate transportation, and there are even some providers on site who can set people up with housing and employment.

But a lot of the services require trips around town at different times of the day.

Sheehan said resources need to be more accessible.

“If we want to say that everyone has a chance to get out of homelessness if they just have the right resources — well, the resources need to be where those people are. It has to be on-site, on-demand,” she said.

As it’s designed, she said, the system doesn’t provide enough opportunities for people to pull themselves out of homelessness.

And the pandemic is just another reminder of how precariously close each one of us is to losing a job or a home.

Lex Treinen is covering the state Legislature for Alaska Public Media. Reach him at ltreinen@gmail.com.