Chunk Bundrant, one of the founders of America’s largest seafood company, Trident, died last month.

He started out as a deckhand on an Alaska crabbing boat in the 1960s and went on to become one of the most influential seafood executives in the world.

Listen to this story:

Today, Seattle-based Trident Seafoods owns more than 40 vessels and operates plants in nearly a dozen Alaska communities.

But at age 19, Bundrant didn’t intend to make a living in the seafood industry when he got his first job as a deckhand.

“He was pre-veterinary medicine down in Middle Tennessee State and he — you know, it’s expensive,” said his son, Joe, who has been Trident’s chief executive since 2013.

Bundrant wanted a job that would pay for his education. So in 1961 he drove from Indiana to Seattle, where he landed a deckhand job.

“No, he never went back to — never went back to college,” said his son Joe, laughing. “Hardest working human being. I’ve met a lot of people in my life, a lot of really amazing people. But I’ve never met any human being on the planet that would outwork that man. Never.”

Bundrant and two other fishermen, Kaare Ness and Mike Jacobson, founded Trident in 1973 with one boat, the 135-foot Billikin, which was the first Alaska vessel to catch, process and freeze crab at sea, according to the company.

“They actually extracted all the meat from the shell,” Joe said. “Put in 15-pound long john containers, and we froze it.”

Around that time, other Bering Sea crab fishermen were on strike to secure better prices from processors. But Bundrant and his partners worked through the strike. The Seattle Times reported that they caught millions of pounds of crab over the next five years, and soon after teamed up with a Bellingham-based processor, San Juan Seafoods.

Trident’s first years coincided with the passage of the Magnuson-Stevens Act in 1976, which forced foreign fleets out of fisheries that extended 200 miles offshore.

Bundrant’s competitive nature and long-term view directed Trident’s trajectory. In the 1980s, he took advantage of the Bering Sea’s huge schools of pollock, which was not a popular fish in America at the time. U.S. Sen. Lisa Murkowski, in a floor speech last month, said Bundrant took risks on land to cement his investment in the whitefish.

“He studied the Japanese methods for catching and processing pollock, he strategized about how Trident could enter this market,” Murkowski said. “Then, in 1981, he took a pretty bold move: He built a plant on a very remote Aleutian island, Akutan, for onshore processing for crab, salmon and, of course, pollock.”

In one of his most notable business maneuvers, Bundrant struck deals with many of the country’s leading fast-food chains, like McDonald’s, to switch their fish sandwiches from cod to pollock.

Bundrant was also involved in fisheries legislation. He pushed for the passage of the American Fisheries Act in 1998, which divided the derby-style pollock fishery into catch shares awarded to individual companies.

As the chief executive of Trident, Bundrant was known for running a tight ship and emphasizing the importance of his employees.

“I take more pride in having somebody that’s been with me 10 years and 12 years and 15 years,” he said in a 1989 video, which was shared during a Nov. 3 celebration of life service. “They become like a family. This company, no matter what size it ever becomes, it’s going to be still a close family. That’s the attitude that management’s going to maintain and that’s the key to Trident’s success, is it’s people.”

[Sign up for Alaska Public Media’s daily newsletter to get our top stories delivered to your inbox.]

Bundrant made lasting connections during his early years in Alaska, too. Among those connections is PenAir founder Orin Seybert, who remembers meeting Bundrant when he fished in Chignik.

“Of course, he was just another fisherman, just a kid actually, in those days,” Seybert said. “But over the years, he got into the crab business. Of course, a lot of my flying was supporting that crab industry.”

In December of 1968, Seybert was flying a mail route when he crashed on an Aleutian island, injuring his leg and gashing his head.

Bundrant was fishing nearby when word went out that Seybert and his passengers were stuck.

“He heard about the problem and he dropped his fishing, steamed into Pauloff Harbor, picked us up,” Seybert said. “It was me, a doctor and two nurses — four of us — and took us into Cold Bay, 40 miles away, but no other way to get there. So we’ve had a special relationship ever since that day.”

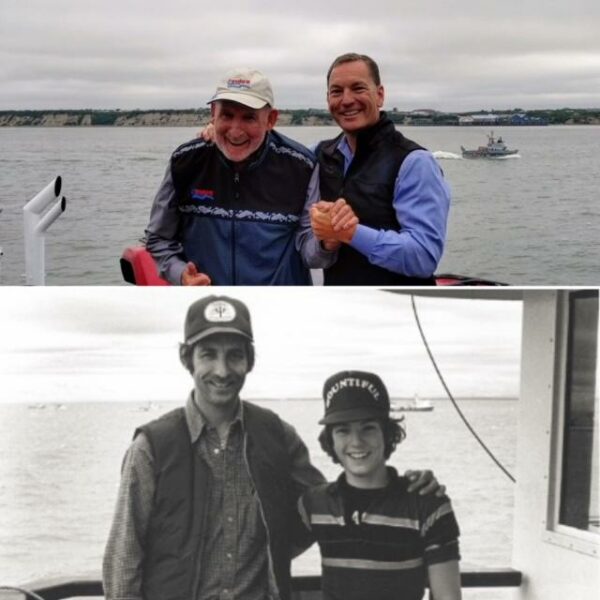

Joe Bundrant said his father first came to Bristol Bay in 1979. Since then, Chuck Bundrant traveled to the region every summer except for 2020. Trident has a plant in Naknek. This summer, Bundrant took his last trip to the bay with his son and grandson, who fishes here now.

“I knew my dad’s health was continuing to fade, and I told him, ‘I don’t care if I have to strap you on my back and carry you pops, we’re going again,'” Joe said. “And he gave me two thumbs up and back to Alaska we went. So Bristol Bay was one of our stops. It’s something that’s just part of my soul, to be able to do this with my dad one more time was abundantly special to me.”

Bundrant served as the chair of the company’s board until his death. Forbes Magazine estimates he had a fortune worth at least $1.3 billion when he died.

Bundrant was diagnosed with an atypical form of Parkinson’s, a degenerative disease, over a decade ago. He died at home in Edmonds, Wash., at age 79.

Contact the author at izzy@kdlg.org or 907-842-2200.