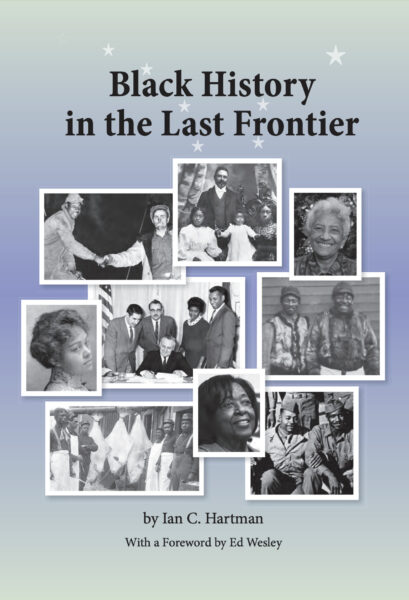

Stories of housing discrimination in the 20th century are often set in the lower 48, but Alaska has its own legacy of racial segregation. In his book “Black History in the Last Frontier,” Ian Hartman outlines how racial segregation looked in Alaska compared to the rest of the country.

For example, housing covenants in Anchorage and Juneau prohibited the sale of houses to anyone who wasn’t white. In some instances, they were specifically written to exclude Black Alaskans and Alaska Native buyers. And in some areas, those historical boundaries impact the ways that neighborhoods look today.

“In Juneau, again, with with the largest minority population being Alaska Natives, you’d probably find very explicit references forbidding the sale of a home to anyone who was not of quote ‘Caucasian extraction’ or whites only are able to sell or whatever the case would be. And then there would be these exclusionary clauses that would encapsulate the various minority populations,” he said.

Hartman is a history professor at the University of Alaska Anchorage. He said it took him some practice to know what to look for while he was looking through historical documents because the racial language was often extremely outdated.

“You have to kind of train your eyes to read these documents, but entire neighborhoods in Anchorage really bear the imprint of racially exclusive buying,” he said.

In 1948, the Supreme Court ruled that racial covenants like these were unconstitutional. That opened the door for Black families to move in. Hartman’s book details that in Anchorage, white supremacists burned down the homes of those pioneering Black families. Those fires, and the pushback from Black activists, led to the NAACP opening its first branch in Alaska in 1951.

In November of 1969, Ebony magazine printed an article saying Alaska’s prospects were open to Black Americans who were willing to work hard. However, the magazine also acknowledged that Black men were excluded from the fishing industry in Ketchikan, and Black Americans and Alaska Natives talked about encountering housing segregation in Juneau, Anchorage and Fairbanks.

Hartman’s book also details instances where Black Alaskans faced further discrimination and racial hostility in the 1970s and 80s as more and more white people moved to Alaska from the South and brought white supremacist views with them.

“I think that there’s a belief among Alaskans, right? The famous line, we don’t, we don’t care how they do it Outside, or, you know, we’re going to do it our own way. And that can have quite a costly impact on communities of color who may be steamrolled by the process — particularly again, in the Cold War era when Alaska really boomed in terms of its population. Then, of course, again, with the with the establishment of the trans-Alaska pipeline in the oil boom in the 70s,” he said.

But the 70s were also the time when Alaskans elected their first Black politicians.

The first Black state representative pushed for a committee to develop a survey on discrimination in Alaska — the group focused on Southcentral Alaska. Hartman details that final report, which showed high levels of housing segregation. It concluded that white residents had deliberately locked minorities out of the housing market and pushed them onto the least desirable land.

Hartman says he wrote the book after years of reading the same stories of the history of Alaska, which left out whole communities of people. And he says that while there’s a historical era of racial tension that has to be confronted, it’s also important to be realistic about the present.

“If you were to look at life expectancy, access to health care, access to quality education, generational transfers of wealth, things like that, I mean, you know, Alaska still does bear the imprint of the historical legacy of, of racism and racial inequality,” he said.

Hartman says he wants people who read his book to see the value in the state’s diversity. He’s expanding on his 2020 book with a new edition set to come out in the fall of 2022 “Black Lives in Alaska: A History of African Americans in the Far Northwest.”

[Sign up for Alaska Public Media’s daily newsletter to get our top stories delivered to your inbox.]

KTOO is our partner public media station in Juneau. Alaska Public Media collaborates with partners statewide to cover Alaska news.