The commander of the U.S. Army in Alaska says his top priority is bringing down the increasing rate of suicide among soldiers stationed in the state.

That’s after the numbers jumped from eight suicides in 2019 and seven in 2020 to 17 in 2021 that are either confirmed or suspected suicides.

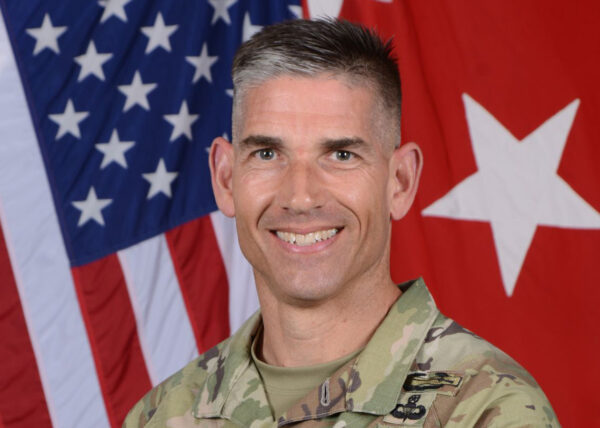

Maj. Gen. Brian Eifler says it’s a problem he and other top Army officials are thinking about and working on every day. He says there are some specific things about Alaska that factor in, but often it’s other issues in a soldier’s life that are exacerbated by being stationed in the north, in most cases far from home, that become contributing factors to depression and hopelessness.

Listen:

[Sign up for Alaska Public Media’s daily newsletter to get our top stories delivered to your inbox.]

The following transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Maj. Gen. Brian Eifler: Being away from the Lower 48, for example, and it’s very expensive to get a flight, especially in the wrong season, right? To get back to family, you can’t just get in your car and drive, it sort of contributes to the stress. You know, some people don’t handle the extreme temperatures well, and so that can play on people’s, you know, whether it’s depression, lack of vitamin D, all those things that can contribute to the stressors of maybe something else that’s going on. I haven’t seen where it’s, “Oh, it’s Alaska, and because of this,” it’s usually something else, like a relationship or inability to cope with the situation that they’re in. And it’s magnified because of the environment.

Casey Grove: You do hear people talk a lot about the darkness in the cold. You can see how, layered on top of other problems, that would be…

BE: I think that’s fair. I mean, it is, I say, Alaska is not for everybody. And it is a tough place for people to live. It’s full of tough people that live in Alaska. And the environment here is something that a lot of people, and a lot of our soldiers, love. They want this adventure. But there are a few that don’t do well. And in some cases, it doesn’t matter where they’re from. There’s people from Miami, Florida, that love this place, that love going up and living in Fairbanks. And then there’s some that don’t.

So one of the other things that we’re trying to do with the Army is bring people here that are are more conducive, and more interested, in serving in an environment like the Last Frontier. I mean, it is called the Last Frontier for a reason. Some people probably shouldn’t come to Alaska, because of some things in their life or some challenges that they’re facing. And we’re a people first Army. So we’re really taking a look at, OK, how do we really put people first? How do we get away from the bureaucratic, you know, “Here, everybody gets this amount of people,” and in just sort of salami slices across the service, to treat Alaska different, and to make sure the people that come here are the people that will thrive here.

CG: The higher rates, the suicides that you’ve seen in Alaska, is that related to combat stress in any way?

BE: Ironically, no. What we see is the inability to cope. And we’re not talking about necessarily that’s related to PTSD for combat, it could be PTSD from something that happened in their life previously. But we can treat for that, right? And then we just got to get people the help that they need to “struggle well,” as we say, through that and get better on the other side. And so, yeah, years ago, PTSD from combat was a big issue, but not so much now, where the Army is largely not in combat as it was before, especially the brigades here in Alaska, where they were rotating back and forth to Afghanistan and Iraq for years. And that really stopped a couple years ago. And so a lot of our challenges are with the younger force. We have some folks that struggle with just coping with life, in relationships, and we can help them with that.

CG: I’d read something, too, that the Army was looking at folks that had been stationed in Alaska, and within the first year of them coming here that they had struggled a little bit more than the other folks. Is that true?

BE: Yeah, I think, as with any type of, you know, like a new job, or a new place that you move to in life, you’re always looking, especially in the Army, we’re always looking really hard at how we receive and integrate new soldiers and families. I think we can always do better with that. And I think, if you’re coming into Alaska in summer, it’s a much better transition than if you’re coming in the middle of winter. That can shock the system. A nice, beautiful, awesome Alaska spring or summer to come into is a great transition. So how we bring people in, the season we bring them in — sometimes we can’t help — but we really got to look at how we bring people in and get them sponsored properly, help show them around, resources. We have a reception center for our new soldiers both here and up in Fairbanks, so that we sort of accommodate them to, “Here’s all the things that you need to know about Alaska. Here’s all the things that you need to do for your vehicle. Here’s all the things,” and a lot of the stuff, we try to do before they get here. But we do want to make sure that they integrate well. The first six months are really critical. And, yeah, you want to get them through the first winter, right? And make sure they’re OK. So I think that first year is always something that we look close at.

CG: I wonder what other things is the Army doing toward this? I had seen everything from vitamin D supplement packs to better recreational facilities.

BE: Yeah, well, you know, educating the soldiers that, “Hey, how do you get a vitamin D check?” Well, usually you have to draw blood, and we really don’t need to do that, you can just get your supplements and take vitamin D. It’s very simple, right?

But more importantly, what we’re really trying to do is get soldiers connected. Sometimes soldiers want to sit in the barracks or sit at home and not go out and do anything. And we want to get people and their buddies to come grab them, and, “Hey, come on, let’s go. Let’s go do this. Let’s go have some fun. Let’s go see a glacier. Let’s go do this climb. Let’s go on this hike. Let’s learn to ski, snowboard,” which you can do at all our installations. I think we need to help our soldiers get out more and do some of those things. Again, most do. There’s a percentage that don’t. And we’ve got to help them with that.

So we started a Mission 100, which is basically our mission. You know, military terms, you give soldiers a mission, and they’re gonna go accomplish it. And the Mission 100 is about a connection. One hundred percent is the term. Everybody connected. We might not be able to prevent suicide, Casey, but we can lower it. We can save some people. We might not save everybody. But we can save a lot of people. And by being connected, like I said, giving some people hope and remaining really aware of our surroundings and seeing signs of people. That might be, “Why did Casey just go over there, hanging out? I can see what’s going on.” It’s just being engaged, and especially coming out of COVID, where everybody’s isolated, that didn’t help.

The other thing we’re doing to overcome the stigma of asking for help is we’ve got counselors, and military family life counselors, that are basically in all our installations, in every unit, that are technically off the books, in other words, there. If you go see an “M-flack,” as we call them (for MFLC or Military and Family Life Counselor) there, they have no military record of it. So it’s safe. So if you wanted to talk to someone, you didn’t want it to go on your record or something like that, or you’re concerned about your career, or your advancement, they don’t even take notes. But it’s someone to talk to and someone that can help. And so what we’ve done is basically said, “OK, everybody, including me, will go get counseling from one of these MFLCs.” And the feedback — again, it’s all non-disclosed and it’s no names or anything — but the feedback we get from the counselors is like, “I’m seeing this many people this week, and half of them really needed to see me, and they would have never came in had we not started this program and mandated everybody to go.” Or some of them are coming back for a second session, or some of them are bringing their spouse in, because they want to get relationship counseling. So we’re seeing that create an understanding, overcoming the stigma, and then more importantly, getting people help and providing them a resource that’s available. So that’s part of the Mission 100 and reaching out. And we think as we continue to do that, I think we’re we’re making some progress.

CG: Are you running into obstacles with trying to get therapists in the Army to Alaska?

BE: Yeah, that’s been a challenge. I mean, it’s a challenge in Alaska in general. We do not have a lot of our clinician positions filled traditionally, we never had in the Army in Alaska. And so we are looking at, the Army is looking at, as well as the Department of Defense, looking at how we can incentivize it better to bring people into Alaska from the Lower 48 that want to stay here and work. Then, in some cases, we have DOD civilians and stuff like that, converting them to military positions to bring more of the military flavor here, because it is hard to get the full manning of our behavior health folks in Alaska, particularly more so even up north in Fairbanks.

Casey Grove is host of Alaska News Nightly, a general assignment reporter and an editor at Alaska Public Media. Reach him at cgrove@alaskapublic.org. Read more about Casey here.