The State of Alaska has released letters, emails, and other documents related to the Alaska National Guard scandal (175 MB). A “privilege log” listing why some details in the documents were redacted was also released.

Copies of all notes, correspondence, memos and emails related to sexual assault in the Alaska National Guard were requested in May by Alaska Public Media. It took until Sept. 26 for Gov. Sean Parnell’s policy director, Randy Ruaro, to deny the request. Records requests are supposed to be fulfilled within 10 days. The state can take an additional 10 days to respond to large or complicated requests.

Alaska Public Media and Alaska Dispatch News sued the state Oct. 8. Two weeks after filing the lawsuit it appeared that the state was willing to release the documents without litigation. A week later the state had only released few of requested documents.

The media organizations advanced their lawsuit Wednesday to force the release of the documents before the Nov. 4 election. Alaska Superior Court judge Gregory Miller ruled on Thursday that the state was to comply with the records requests by Friday at noon. Reporters received a 596-page document around 1 p.m. today.

An initial review of the packet shows a mix of emails, letters, and memoranda. Some are released in full, some are partially redacted, and others are blacked out entirely.

The documents cover a period from August 2009, when then-Brigadier General Thomas Katkus expressed interest in leading the Guard, to September 2014, the month a team of federal investigators from the National Guard Bureau’s Office of Complex of Investigation released its damning report. The report documented favoritism, fraud, sexual assault, and violations of victim confidentiality.

A handful of National Guard leaders, including Katkus, and a deputy commissioner for the Department of Military and Veterans Affairs have since been asked to resign their positions.

While key details are missing, the documents do provide some sense of how the Parnell administration handled complaints about National Guard leadership.

“The Command Climate Has Deteriorated”

A number of problems within the National Guard predate the Parnell administration, with an inquiry from 1995 even finding distrust of the chain of command. Concerns escalated shortly after Katkus’ appointment to the adjutant general position in 2009.

Beginning in 2010, a group of four National Guard chaplains – Matthew Friese, Ted McGovern, Rick Koch, and Rick Cavens – approached the Parnell administration with complaints about leadership.

On January 6, 2011, Cavens submitted a letter to the governor describing an “intense pall of despair” within the Alaska Air National Guard as a result of “upper levels of leadership … cut[ting] hope and spirit by manipulation and passive aggressive behavior.” The letter describes the Clear Air Force Station as a location to “store officers of sexual infidelity,” and that the colonel responsible, Donald Wenke, would look the other way when one guardsmen in uniform would “get drunk and make advances on enlisted women.”

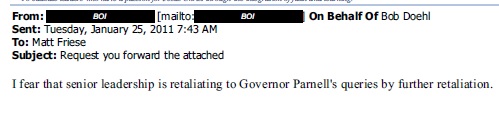

A letter dated January 25, from Bob Doehl, a lieutenant colonel who now serves as an aide to Democratic Sen. Mark Begich, expresses concern that senior leadership is retaliating in response to queries from the governor’s office about the command structure.

A September 24 email from Brig. Gen. Chuck Foster, who commanded 176th wing of the Alaska Air National Guard, alleges he is being pushed out of his job by Katkus and asks the governor to help him keep his membership in the Guard.

“I believe that the command climate has deteriorated even further, and unless the course is altered it will not improve,” Foster wrote. After losing his position to Wenke, Foster was transferred to headquarters, where he lasted only three months.

“It was very clear that Gen. Katkus really didn’t want me at the headquarters, that he really didn’t have a place for me,” Foster said in an interview on Friday. “Nizich seemed attentive to what I had to say. He engaged with me, he listened to me, but basically nothing came of it.”

A December 29 letter from chaplain Friese likens participation in the Guard to “an abusive relationship.”

Throughout 2011, Friese operated as the primary conduit for complaints about Guard leadership to Parnell Chief of Staff Mike Nizich. The packet contains 18 separate emails from Friese to Nizich, and a dozen more are identified in a log provided by the Department of Law. Nizich’s responses to the emails were typically brief but timely, particularly toward the beginning of their communication.

When concerns about confidentiality are first raised on February 14, Nizich stressed that no details had been turned over to Katkus nor would they be. On December 22, chaplain Cavens charged that Nizich provided information to Katkus. Nizich denied the accusation then, and today maintains that trust was never breached. In a follow-up email between Nizich and Friese, the two attempt to repair the line of communication, and one chaplain offers “most sincere apologies.”

After a phone call between Nizich and two of the chaplains on December 29, no further records of communication between the chaplains and Parnell’s office appear in the email log.

“A Problem That Could Bite Us Both”

In 2012, the Parnell administration received several inquiries from Sen. Mark Begich’s office about their response to National Guard problems. On January 25, just one month after discussions with the chaplains broke down, Begich chief of staff David Ramseur sent Nizich an email asking to discuss the matter.

“I need to tell you what we’re picking up as it sounds like a problem that could bite us both,” Ramseur wrote.

In March, Ramseur requested another conversation, and this time attached an anonymous letter from a group labeling itself “Friends of the National Guard” and datelined Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson.

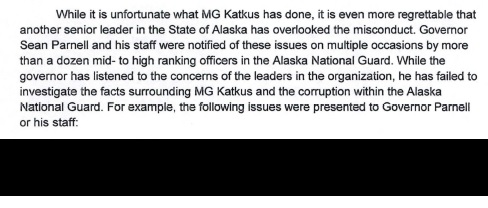

The letter described Katkus as a “corrupt leader” and also criticizes the governor.

“While it is unfortunate what MG Katkus has done, it is even more regrettable that another senior leader in the State of Alaska has overlooked the misconduct. Governor Sean Parnell and his staff were notified of these issues on multiple occasions by more than a dozen mid- to high ranking officers in the Alaska National Guard. While the governor has listened to the concerns of the leaders in the organization, he has failed to investigate the facts surrounding MG Katkus and the corruption within the Alaska National Guard. For example, the following issues were presented to Governor Parnell or his staff: [redacted]”

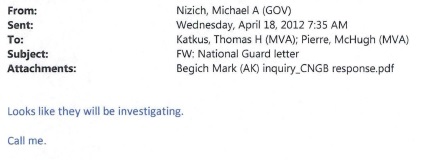

In April, Ramseur gave Nizich a heads up that the Departments of the Army and Air Force had been made aware of complaints about the Guard, and that the inspector general was looking into them (at Begich’s request). “Looks like they will be investigating,” Nizich wrote to Katkus shortly after being notified. “Call me.”

Little came of it. The team mentioned that there were anonymous reports of “sexual assault victims not coming forward,” but they did not identify any grievous problems with the Guard.

When investigations into the Guard made headlines in 2013, Katkus responded with a dig about Begich, and suggested the junior senator was grandstanding on the significance of it:

“Begich’s statement … is a bit disingenuous. … Their only area of concern in their findings centered on how we did data entry in their new tracking system, which we quickly corrected.”

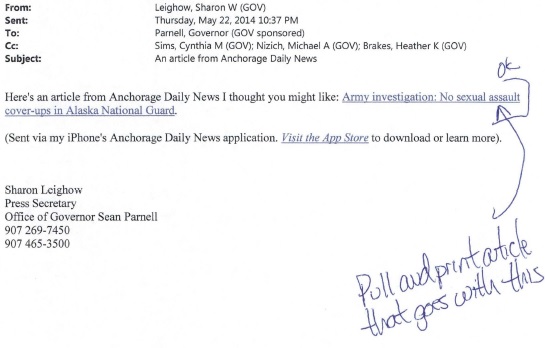

An inspector general investigation requested by Republican Sen. Lisa Murkowski in 2013 was also fruitless. When the results came back in the spring of 2014, members of Parnell’s staff welcomed them. Stories about the findings were passed on to the governor and posted on the official website. “Here’s an article from the Anchorage Daily News I thought you might like,” the governor’s spokeswoman Sharon Leighow wrote in an email. “Army investigation: No sexual assault cover-ups in Alaska National Guard.”

It wasn’t until investigators from the Office of Complex Investigations came in at Parnell’s request in February that wrongdoing was uncovered.

In an emailed statement, Nizich notes that the OCI investigation was not the first requested by the Parnell administration.

“In October 2010, I contacted the FBI requesting an investigation into a series of allegations that included: assault, sexual abuse, misuse of resources, drug trafficking and transporting illegal weapons. The FBI special agent who conducted the six-week investigation was Special Agent Kevin Fryslie. After approximately six weeks, I placed several calls to his office and he finally reported to me that there was nothing to the allegations.

Despite the lack of findings in that investigation and 3 other federal investigations, Governor Parnell called for a fifth investigation in February 2014 that finally uncovered the serious problems in the Alaska National Guard.”

Our Lane’s Been Investigated

With investigations coming up dry, emails from administration staff in response to National Guard allegations took on a more skeptical tone.

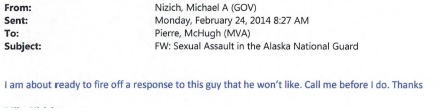

The office regularly received complaints from Chris Bydalek, a former contractor with the Guard. On February 24, 2014, Bydalek sent an angry email with the subject “Sexual Assault in the Alaska National Guard” that aggressively calls out Katkus and accuses the governor of doing nothing. Nizich forwarded the email to deputy commissioner McHugh Pierre.

“I am about ready to fire off a response to this guy that he won’t like,” Nizich wrote. “Call me before I do. Thanks.”

That same week, Bydalek sent another message accusing Katkus and Parnell of covering up wrongdoing. In a separate exchange about it, Katkus writes that all “the issues in our lane have been investigated” and Nizich responds by asking if they have a photo of Bydalek on file.

In May, Bydalek sent an email to a half dozen members of the administration that describes a female member of the Guard being threatened and mentions Katkus’ name in the context of retaliation. When Nizich forwarded the email on to a federal investigator, he noted it was the “same type of information we heard before without any specific facts to back up the claim.”

Both Katkus and Pierre were asked by the governor to resign after the OCI report substantiated allegations of fraud, mishandling of sexual assault, and misuse of government property.

By the time this story was published, the Department of Law had released an additional 116 pages of records. It is expected to provide more documents Saturday.

Alaska National Guard emails – 175 MB pdf

Privilege Log – 58 KB pdf

agutierrez (at) alaskapublic (dot) org | 907.209.1799 | About Alexandra

Jennifer Canfield is a reporter at KTOO in Juneau.