In 1962, the Douglas Indian Village was set ablaze to make way for a new harbor. This month marks 53 years since the city displaced households of Tlingit T’aaku Kwáan families. Little to no restitution has ever been offered.

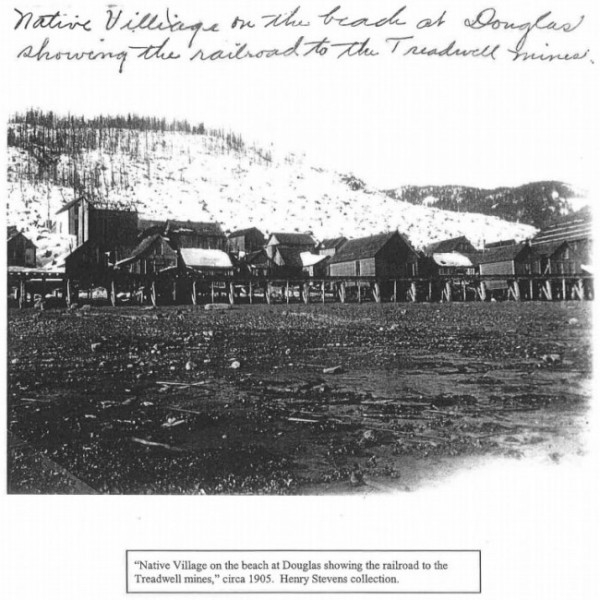

The Douglas Indian Village was a winter spot for the T’aaku Kwáan people. Water flowed underneath a row of about 20 structures on pilings. There was a saying, “this was where the sun rays touched first.”

The village had no running water or electricity. But to John Morris it was home.

“That was the trail I used to walk to go to school right here. But my house was right where that truck is right now,” he says.

Where we’re standing has been filled with gravel. The water no longer comes up to this point. It’s been turned into Savikko Park, a place where children play Little League and families grill out hamburgers.

Morris remembers seeing his childhood home here going up in smoke.

“We left everything as is in the house with the thought that if they saw that we hadn’t moved anything out that they would maybe prolong the burning. It didn’t stop them.”

Fishing nets, clothing, dishes–everything.

“There are no pictures of my childhood. It was all burned up in that house,” he says.

Morris is a carver, teacher and tribal leader. At 75 years-old, he’s also one of the last living members of the tribe to witness the burning of the village in 1962. He remembers, back then, racial tensions were high. He delivered newspapers as a kid.

“And I had a paper sack that had Juneau Empire on it. And as long as I had that paper sack I could go anywhere in Douglas. Once I took that sack off people would tell me, ‘Get down to your village.’”

In 1946, the Douglas Indian Association was looking for boat loans. At the time, boats were kept under the house. But that wasn’t deemed suitable. So the city and the Army Corps of Engineers were asked to build a harbor where the village stood–with the understanding the village would be rebuilt.

That plan didn’t go anywhere.

“But the plan for the harbor stayed on the books and in 1962, the City of Douglas destroyed the Indian village to build that,” says attorney Andy Huff. He put together a formal report in 2002 on what happened for the Montana Indian Law Resource Center.

Back in the ’60s, the City of Douglas found a loophole to condemn the Native village: Most of its occupants were gone to fish camps in summer.

“Even so, the city didn’t have jurisdiction over the houses in the first place. It was a federally protected enclave.”

Huff says when he was doing his research, two more red flags stood out. One was the Bureau of Indian Affairs, the agency that’s supposed to help, did nothing to intervene.

“They just flatly refused to get involved even though there was this plan to kind of destroy the village,” Huff says.

The other red flag was a possible conspiracy.

“I found that two members on the city of Douglas zoning commission, which was the entity in charge of destroying this village, were also members of the Bureau of Indian Affairs at the same time. ”

They were Charles Jones and A.W. Bartlett. Both men resigned from the zoning and planning committee citing conflict of interest. But the plans to burn the village were already underway. Huff says that’s an obvious breach of trust. When he put the report together 13 years ago, he thought it would affect change but no restitution has been offered. He thinks, even after all this time, there’s still a legal case.

“I don’t think the federal government can argue it doesn’t know exactly what happened and what the issues are in light of the report coming out and being released by the tribes,” he says. “Something should have happened by now.”

The Bureau of Indian Affairs could not be reached for comment.

After the controlled burn in 1962, the village was never rebuilt. The Douglas Harbor and eventually the park were constructed in its place. Morris, who was on military leave at the time, says he went back to Fort Hood, Texas, changed.

“I went back with a bitterness. A bitterness that I’m not going to have anything to come back to. I don’t have a home. The people I grew up with, I got to see firsthand, how they treated us people, us Natives,” Morris says.

It took years for him to come back to the Juneau-Douglas area but he did. He says sometimes friends tell him he should file a lawsuit; he could be a millionaire.

“My response is that’s not what I’m after. I do want to see that corrected but it will never leave me. It will never leave me. It lays dormant and I don’t like to touch it unless I have to,” he says.

Morris says he forgives but he doesn’t forget. He would like to see restitution for the T’aaku Kwáan people.