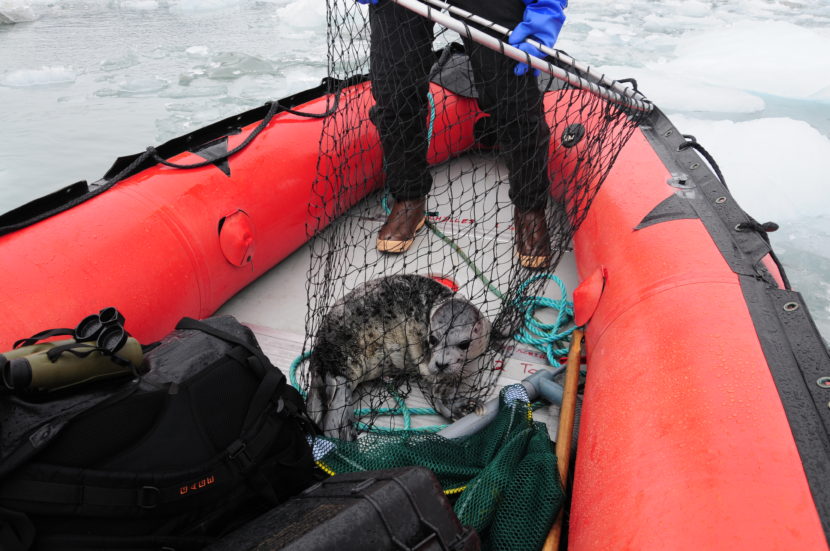

enough to net a seal. (Photo by Jamie Womble, National Park Service)

Summer is an important time for seal pup development. So the federal government is asking vessels — like cruise ships — to stay farther away from harbor seals in glacial fjords. Biologists are tracking the population in Disenchantment Bay near Yakutat to see how the new guidelines are working.

Tagging 45 baby seals is no easy task. That’s the number John Jansen, a federal biologist, has in mind. His crew is preparing to float through the water near the face of Hubbard Glacier.

The plan: Catch the pups as they drift by on hunks of glacial ice.

“Our first attempt is going to be using a small dip net and trying to approach them in a stealthy way,” Jansen said.

Of course, mama seals can make this difficult. It’s easier if they scoop up a pup before she notices they’re around. Once Jansen and his crew catch a seal, they’ll glue a satellite transmitter to its fur, either on its back or head.

“Because that’s the only part that typically comes out of the water when they’re at sea. Those have been equated with party hats,” he said with a laugh.

Back in his Seattle office, Jansen will be able to see the pup — just a small dot — on his computer screen. It sounds like a seal version of Big Brother, but the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration wants to know how much time pups spend hauling out on the ice. It’s an important time for seals to rest. And for baby seals, it’s a chance to fatten up.

“There is a really critical function of hauling out, and if that period of hauling out is disturbed by humans, it has a consequence,” Jansen said.

As many as four cruise ships a day can be in Disenchantment Bay. It’s a popular spot to see massive hunks of the Hubbard Glacier fall into the water. Seals rest on icebergs nearby.

But the ships sometimes scare seals into the water.

“In Yakutat, we harvest seals so the seal population has to stay healthy,” said Victoria Demmert, the president of the Yakutat tribe.

She said local hunters became concerned in the late ’90s when they noticed fewer seals in Disenchantment Bay. And they wondered if an increase in tourism was affecting the population. So NOAA started monitoring the seals. Over the years, the federal agency has observed large vessels are causing the seals to spend less time on the ice.

Demmert said that’s a growing concern for the tribe.

“We understand they want to show off the area for their passengers but we need them to be considerate,” Demmert said.

The old marine viewing guidelines advised vessels to stay 100 yards away from seals. They were created before the boom of tourism. Aleria Jensen, a NOAA stranding coordinator, said that’s no longer adequate in glacial fjords. So the agency came up with new guidelines and took public comment.

NOAA had two options: Make it voluntary or require it through regulation.

“The agency decided to go with a voluntary approach. So there are some measures that are meant to apply to glacial fjords across Alaska,” Jensen said.

Vessels are now being asked to stay 500 yards away from seals. Jensen said NOAA realizes the tour industry offers the state a significant economic boost.

“And the goal here is to protect seals without compromising opportunities for high quality glacial viewing and wildlife viewing experiences but finding the balance,” Jensen said.

Soon, NOAA and the National Park Service will be closer to figuring out what that balance is. They’ll use this summer’s research to determine exactly how the vessels impact the growing seals. For example, how much time are they really spending on the ice?

Back in Disenchantment Bay, John Jansen and his team are giving a seal pup a haircut. Actually, they’re taking hair and whisker samples to bring back to the lab. Then they glue on the tracking device.

“We just want to make sure that the rise and presence of humans is not putting those populations at risk,” Jansen said. “We want to make sure they’re there for everyone to enjoy in the long term.”

After awhile, the seal mom swims around to check on her baby.

“That’s frickin’ awesome!” Jansen said.

When the biologists are finished, they dip the pup back into the water — with new haircut and new hardware.