A new study headed up by two University of Alaska Fairbanks archeologists proves for the first time that people who lived in this area more than 11,000 years ago ate salmon, in addition to big game like bison.

The study is based on a chemical analysis of tissue samples from those ancient people. It provides the most detailed information yet about their paleo diet and culture.

Lead researcher Carrin Halffman said the most important takeaway from the study she co-authored is that it shows the people who lived in this part of Alaska near the end of the last Ice Age had a more diversified diet than was previously known, and that their diet included salmon.

“What I think this study has really done is overturn that traditional notion of Ice Age Alaskans as strictly big-game hunters, focused almost exclusively on the very large animals, like bison and elk,” she said in a recent interview.

Halffman used a technique called stable isotope analysis to reveal that salmon probably constituted about a third of what the ancient people ate during the summer. The discovery of salmon in their diet also confirmed what some members of the team had theorized back in 2015 — that those salmon species had returned to this part of the world as the ice sheets receded.

“It wasn’t until recently that we knew that salmon were even running in the rivers of Interior Alaska at this early date, at the tail end of the Ice Age,” she said.

Study co-author Ben Potter said Halffman’s stable-isotope analysis in turn revealed much about the life of the people he calls Ancient Beringians — the foragers who crossed over the land bridge from Asia to North America many thousands of years ago. Potter said it shows, among other things, that the ancient peoples’ survival strategies weren’t based solely on hunting big game.

“What this study shows is a much more realistic picture of the way these ancient foragers would’ve operated,” he said. “Which is, they’re modern humans, just like us. They’re smart. They’re going to be evaluating what’s locally variable in different seasons.”

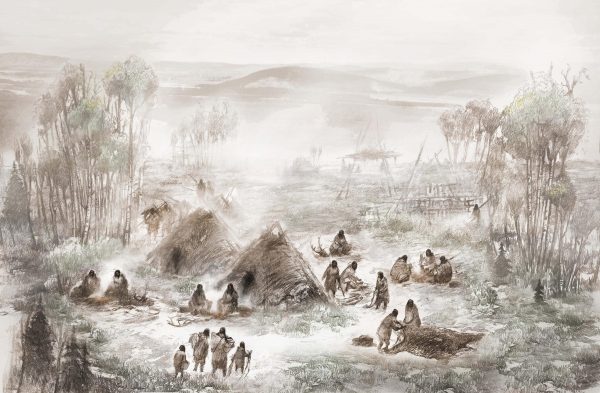

Potter said the study published last month in the journal Science Advances is based on solid archeological evidence derived from the isotope analysis on multiple samples of well-preserved tissue. The samples were taken from two of the ancient people who live at the seasonally occupied hunting camp known as the Upper Sun River site, located near what’s now known as Birch Lake.

He said it’s much more accurate than analyses conducted on animal bones around the campsite, the technique that archeologists have relied on until recent years. Among other things, bones of salmon and other fish often don’t show up using that technique, because they’re less dense than terrestrial-animal bones, and disintegrate much more quickly.

“This is really our first direct glimpse, our first direct measure, quantification, of these ancient paleo diets,” he said in a joint online interview with Halffman.

Potter, who’s now affiliated with the Arctic Studies Center at Liaoching University in China, said the isotopic analysis and other evidence gathered by the 15 researchers who contributed to the study reveal such details of their lifeways. Those include the time of year the people were at the camp – around late July or early August, when the salmon were running.

“That’s pretty cool,” he said. “That’s pretty amazing that we can do that.”

Potter said all that evidence has helped the researchers discern the ancient people’s understanding of the seasons in which food was available, and where to find it at those times.

“This study provides a foundation,” he said, “like a baseline to begin to talk about the possibilities of subsistence strategy, seasonality, movement.”

Those kinds of sweeping big-picture findings are important, said Halffman, an affiliate research assistant professor with UAF’s Anthropology Department. But so too are the findings that the general public can appreciate about the everyday lives of two of those ancient peoples.

“One really interesting aspect of our study is the glimpse that it provides into the lives of two ancient Alaskan women over a very short time period, a single summer season,” she said.

That’s because the tissue samples used for the analysis came from two very young infants who died and were buried at the site. So, Hallfman said, the diet revealed by the isotopic analysis was actually that of the two infants’ mothers.

“I think people can really relate to that time scale, and really imagine these women living in Ice Age Alaska, 11,500 years ago,” Hallfman said.

Potter said the excavations and research at the Upper Sun River Site was conducted with the assistance and support of the Tanana Chiefs Conference and the Healy Lake Tribal Council.

Tim Ellis is a reporter at KUAC in Fairbanks.